Summary Statement

Describes fatalities in roadway workzones, a case study and steps that are being taken to reduce them including a national safety awareness week and a NIOSH report discussing recommendations.

June 12, 2000

|

They are not just statistical losses like the win-loss record of a struggling baseball club. The many hundreds of people killed each year in highway work zone accidents are mothers, daughters, sons and fathers who have had their most precious possession stolen—their life. Some are motorists and truckers who crash while trying to pick their way through the ever-growing number of highway work zones. Others are flaggers, laborers, equipment operators, inspectors, engineers and supervisors employed by contractors and state departments of transportation who are struck by construction equipment on the site or by wayward motor vehicles. But when these victims are unified into a cold, anonymous statistic, the results numb the mind. There were 772 people killed and 39,000 injured in motor vehicle crashes in construction work zones in 1998, the last year for which national data is available. This is slightly higher than the average of 760 people killed every year.

|

|

The industry always has been concerned with the problem, but contractors, contracting agencies and government policy makers finally are coming together to declare war on this carnage.

The issue now will be more visible to the public. The first annual national Highway Work Zone Safety Awareness Week was launched April 3-7 by a broad consortium of construction industry and government organizations to publicize the hazards of construction work zones. And to help get the word out on how to make work zones safer, a National Work Zone Safety Information Clearinghouse https://www.workzonesafety.org/ has been established by the Federal Highway Administration, American Road & Transportation Builders Association and Texas Transportation Institute.

Other agencies also are in motion. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health is about to release a long-awaited final report on work zone safety that will contain recommendations on what roadbuilders, maintainers, contracting agencies and policy makers can do to save lives.

A draft was circulated for industry comment and the final version is different in that it recognizes that "employers" cannot all be lumped together because they do not control all aspects of the work zone, says Stephanie G. Pratt, one of the three NIOSH authors of the report.

That jibes with the common industry view. "Our contractors do not control a lot of the things that a commercial contractor does," says Peter Ruane, president of the American Road and Transportation Builders Association. "We believe there is a need for a more comprehensive approach" to safety.

It is obvious to NIOSH and others that there will have to be a safety alliance to breach barriers to better performance. The contract process is a main focus. "Safety needs to be incorporated into the bid process" to put all contractors on a level playing field, says Pratt.

"We would agree with

that 100%," says Bob Johnson, safety manager of the branch division of

Granite Construction Co., Watsonville, Calif. "We buy top-quality equipment

and a traffic control truck costs $100,000, easy. But we may be competing

against a contractor putting cones out the back of a pickup truck," he

says. "We would love to be spec'd in."

|

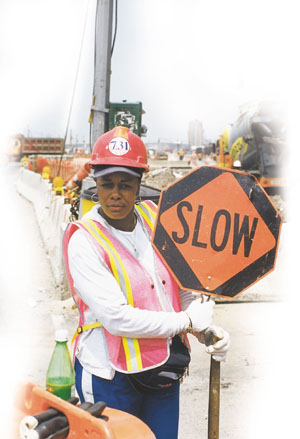

Contrary to

the view of many contractors, NIOSH believes that a much greater

emphasis needs to be placed on control of construction traffic and

equipment in the work zone, rather than the motoring public passing

by. NIOSH also would like to see use of high-visibility clothing for workers required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in the same manner as personal protective equipment. "All workers should wear high-visibility clothing as ppe because it raises [the practice] to a higher level," says Pratt. "A flagger is not a traffic control device....Let's get something in OSHA that takes [clothing] to a level of safety."

|

SEPARATION Barriers give more protection than barrels.

SEPARATION Barriers give more protection than barrels. |

OSHA officials say they are awaiting the NIOSH report with great interest because the agency is launching its own assault. OSHA currently has a "local emphasis program" under way in Region 5 for enforcement of work zone safety, and that likely will be a model for a national program to start by the end of the year, says H. Berrien Zettler, deputy administrator of OSHA's Construction Industry Directorate.

OSHA is compelled to act. In 1996, Congress told federal agencies to develop five-year strategic plans for which they would be held accountable. OSHA identified two goals for construction: reducing injury and illnesses by 15% and fatalities by 15%. "We believe work zones fit" this mission, because highway construction is among the five industrial classifications with the highest fatalities, says Zettler.

The OSHA pilot program is a partnering effort and will deal with "both sides of the barrel," says Bill Grams, executive director of the Illinois Road Builders Association. OSHA was looking mainly at work zones and not autos, but we are "fusing both of these together," he says.

"OSHA has pretty much ignored highway work until now," says Scott Schneider, director of occupational safety and health for the Laborers' Health and Safety Fund of North America. "It is good that they go out and take a look."

OSHA also is about to kick off a highly unusual "direct final rule" process to adopt as a safety rule the Federal Highway Administration's current Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices. Instead of taking the usual four or five years, OSHA hopes to have the final rule in place by the end of the year.

MUTCD is a comprehensive document that governs the motor vehicle aspect of highway work zones. It provides overall direction for the design and setup of work zones, as well as training, personal protective equipment, speed reduction, barriers and lighting. A major revision of mutcd also is due by December, says Janet Coleman, chief of safety programs at FHWA.

NIGHT MOVES Night work reduces traffic disruption, but heightens dangers for crews.

OSHA thinks it can move quickly because it is not opening up mutcd for changes, but only accepting public comment on whether it should be adopted in its entirety. The highway division of the Associated General Contractors supports this move and met with OSHA May 24 to discuss the issue.

"We will put together a joint committee with OSHA" and partner on this issue, says Ted Aadland, president of F.E.Ward Constructors, Vancouver, Wash., and chairman of agc's highway division.

Contractors welcome the action because they currently can be in compliance with FHWA's MUTCD rules and still be cited by OSHA inspectors for a safety violation. OSHA rules incorporate a 1968 version of a predecessor document of the mutcd and "there are significant differences...that sometimes cause conflict," says Zettler.

| Government rules only specify minimum action and some companies are prescribing their own tougher ones. Tragedy is a powerful motivator. Cianbro Corp.'s Clifford Briggs Jr., 49, was struck and killed by a motorist Jan. 14 while he and his crew were loading a backhoe onto a trailer at a pipeline project. He had been with the Pittsfield, Maine-based contractor 27 years. "We learn from these kinds of experiences...that we have to adopt a zero tolerance to all of these issues," says President Pete Vigue. |  |

After the accident, Vigue declared: "If any people are exposed to traffic, there will be a physical barrier to protect them." The barriers can be of various types, but they will be there. "We can set the example to prove to people that it is achievable without sacrificing productivity and work quality," says Vigue. "We have a responsibility to take care of our people in work zones. It has no relevance if someone is speeding...or a driver makes a mistake."

Younger drivers tend to make more mistakes and that prompted the Carolinas AGC and the North Carolina Dept. of Transportation to partner in the production last year of a driver training video, A Sudden Change of Plans, aimed at 16 and 17-year-olds. Two copies were sent to every public and private driver education teacher in North and South Carolina and thousands more have been produced for broader distribution by AGC and FHWA.

"We see the bigger problem [in work zone safety] being the traveling public," says Barry Jenkins, director of the heavy-highway division of the Carolinas AGC. "When drivers are doing two or three things at the same time with dogs, kids and cell phones, they do none well," says Jimmie Travis, NCDOT construction programs engineer.

The tape depicts a teenager listening to music, talking on a cellular phone and otherwise not paying attention as she drives through a work zone. She strikes and kills a construction worker.

"Sometimes you think that you may be stretching reality. But then something happens that makes you realize that reality is even more frightening," says Steve Gennett, executive vice president of the Carolinas AGC. As it turned out, fiction turned into reality.

EYES PEELED Workers on foot near heavy equipment are at particular risk.

When Pete Wert first saw the video last fall when it was introduced at an AGC meeting, he says he thought it was "powerful." But the chairman of Haskell Lemon Construction Co., Oklahoma City, and past national AGC president says that two months later on Nov. 23, 1999, the "identical situation" occurred in a work zone and killed two company employees.

"We were paving in the center median of a divided highway, putting a crossover to move traffic from one side to the other," says Wert. He explains that a very young driver in a pickup truck traveling at a "very high rate of speed" became distracted and swerved across two lanes of traffic and struck the two workers standing on the median. Killed were Randy Space, 35, an asphalt lay-down supervisor, and Henry Cowger, 57, a roller operator.

"We are devastated," says Wert. "For all of the things we are doing in safety...the bottom line is that we are not getting there. The people we are not getting to are the motorists. They are endangering themselves and us."

Wert and other contractors

say the danger is escalated with the shift to night work. "It is dangerous

on its face," says Wert. "We ought to really examine our priorities" and

decide whether motorist inconvenience is so bad.

|

Getting drivers to slow down in work zones is going to be the toughest mission of the war on injuries and fatalities, and law enforcement may provide some of the troops. In New Jersey, a new safety program involves training state police officers about work zones and getting more police cars at sites. "We saw real results right away," says Bob Bryant, executive director of the Utility and Transportation Contractors Association of New Jersey. "If there is a way of slowing traffic down in a work zone, it would make a difference," says George Rossa, safety director for Bishop-Sanzari, Lyndhurst, N.J. "All you have to do is go out to the New Jersey Turnpike and see them flying by work zones at 80 mph." |

|

How Work Zones Can be Made Safer

Traffic Control

- Increase the size of the lateral buffer zone to reduce worker exposure to passing motorists.

- Install low-level transitional lighting in advance warning and termination areas to ease motorists' adjustment to changing lighting conditions.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of traffic control by checking for evidence of near-misses, such as skid marks.

- Use traffic-control devices in a consistent manner throughout the work zone.

- Create positive separation between workers and motorists by using such devices as concrete barriers and truck-mounted attenuators.

- Train and certify all flaggers. They should not be the least-trained employees on the job-site

- Ensure that motorists have real-time information in signage and advisory radio broadcasts.

- Cover or take down warning signs when workers are not present.

- Use an advance media campaign to advise the public of upcoming road work.

- Increase involvement of law enforcement in traffic control.

Internal Traffic Control

- Develop an internal traffic control plan along with the overall traffic control plan, showing the movement of construction workers and vehicles within the work space and providing for a communications program.

- Channelize dump trucks in the work space and keep workers on foot out of that channel.

- Ensure proper lighting within a work zone, controlling glare so as not to blind workers and passing motorists.

- Implement a reporting system for all close calls and incidents relating to the internal traffic control plan.

- Install radar, sonar and ultrasonic sensors on equipment to warn operators of impending collisions with pedestrians and objects.

- Use alarms that are at least 10 decibels above background noise.

Source: NIOSH

Fatality Statistics Are Real People Who Had Lives

|

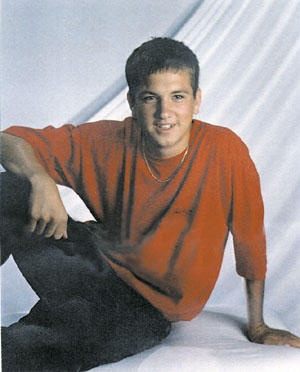

Eighteen-year-old

Travis Ellis loved flowers and gardening -- and that is what killed

him.

Travis had just graduated from Bedding Field High School in Wilson County, N.C., in 1998 and he and his father talked about the possibility of his going on to community college. "He said he wasn't ready and that he needed to work," says his father, Herbert Ellis Jr., of Saratoga, NC One of Travis's golfing buddies told him that there was an opening in the landscape division of the state Dept. of Transportation. "That sounded ok to me, it being a state job," says Ellis. "I never thought something like that would happen." Travis "loved plants [and] always had a garden," says Ellis. He grew his own vegetables and took horticultural classes at school whenever he could. He told his father that he wanted to go to school later to take landscape design, especially for golf courses. |

|

"He was real excited about that job," says Ellis. On Oct. 1, 1998, Travis

had been with the dot for about a week. He was working with a dot crew

of about four people on the median of Highway 7 near Goldsboro, spraying

flowers. The driver of a car traveling about 60 mph in the 45--mph zone

looked down to either write something or talk on a cellular phone and

lost control. He somehow managed to get around the parked dot trucks equipped

with flashing lights and the barrels that marked the work zone and struck

Travis on the median. Travis was helicoptered to a trauma center in Greenville.

"His supervisor and one or two of the boys" that he had been working with

came to the hospital and stayed with him and "dot made us part of the

family," says Ellis. Travis died the next day.

The driver originally was charged with involuntary manslaughter, but was

allowed to plead guilty to death by motor vehicle after Ellis and his

wife Lois talked to the district attorney. They didn't think they could

go through a trial. "I know he didn't intend to run him over," says Ellis.

Travis also liked to cook. While they were making dinner the night before the accident, Travis's mother asked him, "You do wear one of those orange vests don't you?" He replied, "Yes Mama, I do. Don't worry, I'm not going to walk out in front of any car."

Travis's parents participated in the kickoff of the first annual National Work Zone Safety Awareness Week April 3-7 in Washington, D.C. "We're trying to make the public more aware. I drive through a work zone every day and drivers don't pay any mind. They don't even slow down," says Ellis.

"I think the state dot is trying to do something" about the problem, says Ellis. "I hope it carries over to everyone. There are other Travises out there doing a job. [The accident] made me realize how dangerous it is out there. You think it can never happen to you, but it can."