Evidence Based Review of the Current Guidance on First Aid Measures for Suspension Trauma

Summary Statement

A review and recommendations by the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) on advice and guidance available on suspension trauma.

2009

Prepared by Health and Safety Laboratory and the University of Birmingham for the Health and Safety Executive 2009

Dr A Adisesh, L Robinson, A Codling & Dr J Harris-Roberts

Health and Safety Laboratory

Harpur Hill

Buxton

Derbyshire SK17 9JN

Dr C Lee & Professor K Porter

University of Birmingham

Academic Department of Traumatology

Institute of Research and Development

Birmingham Research Park

Vincent Drive

Birmingham B15 2SQ

hmsolicensing@cabinet-office.x.gsi.gov.uk

In 2002 the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) published a review entitled ‘Harness Suspension: Review and Evaluation of Existing Information’. It was noted in this report that the rescue plan was an essential part of fall protection arrangements. The report quoted and summarised advice extracted from various papers concerning harness suspension and noted that, ‘some of the advice appears to conflict’. Nevertheless, although this document was not intended to be a review of the medical advice for rescue from suspension it has been frequently cited in such a context and in support of measures that differ from standard UK first aid practice. Consequently, it was the recognition that authoritative guidance was needed for first responders, in the workplace setting, to any cases of a fall into harness suspension, which led to this project being undertaken.

The Health and Safety Laboratory (HSL) was asked to review the advice and guidance available on suspension trauma. This review was used to address the questions of whether the current information and advice available for treating suspension trauma casualties was adequate and in line with current practice and recommendations, and whether there was a need for HSE to produce guidance.

This report and the work it describes were funded by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Its contents, including any opinions and/or conclusions expressed, are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect HSE policy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors of the report would like to thank all those that contributed to the project and the compiling of this report. This included HSE colleagues and invited stakeholders that attended and contributed to the workshop held at the Health and Safety Laboratory on the 30 April 2008. In addition thanks to Lynne Barnes for her help in making the arrangements for the workshop.

CONTENTS

2.1 Evidence Based Review Method

2.2 Literature Selection

2.3 Critical Appraisal of Papers

2.4 Stakeholder Workshop

APPENDICES

-

Appendix 1 - Critical Appraisal Form

Appendix 2 - Evidence Tables

Appendix 3 - Glossary of Terms

Appendix 4 - Stakeholder Workshop Summary and Satkeholder List

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In 2002 the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) published a review entitled “Harness Suspension: Review and Evaluation of Existing Information”1. It was noted in this report that the rescue plan was an essential part of fall protection arrangements. The report quoted and summarised advice extracted from various papers concerning harness suspension and noted that, “some of the advice appears to conflict”. Nevertheless, although this document was not intended to be a review of the medical advice for rescue from suspension it has been frequently cited in such a context and in support of measures that differ from standard UK first aid practice. Consequently, it was the recognition that authoritative guidance was needed for first responders, in the workplace setting, to any cases of a fall into harness suspension, which led to this project being undertaken.

Objectives

The Health and Safety Laboratory (HSL) was asked to review the advice and guidance available on suspension trauma. This review was used to address the questions of whether the current information and advice available for treating suspension trauma casualties was adequate and in line with current practice and recommendations, and whether there was a need for HSE to produce guidance.

The requirement for this work arose because first aid training organisations and first aiders were not clear about the correct positioning of rescued casualties in the event of a harness suspension situation.

Main Findings

There is little scientific published literature regarding the circumstances and consequences of harness suspension, and none that tests the effect of sitting a rescued casualty in the semi-recumbent posture that some authors have suggested.

Main Recommendations

- No change should be made to the standard United Kingdom (UK) first aid guidance for the post rescue recovery of a semi-conscious or unconscious person in a horizontal position, even if the subject of prior harness suspension.

- No change should be made to the standard UK first aid guidance of ABC management, even if the subject of prior harnesses suspension.

- A casualty who is experiencing pre-syncopal† symptoms or who is unconscious whilst suspended in a harness, should be rescued as soon as is safely possible.

- If the rescuer is unable to immediately release a conscious casualty from a suspended position, elevation of the legs by the casualty or rescuers where safely possible may prolong tolerance of suspension.

- First responders to persons in harness suspension should be able to recognise the symptoms of pre-syncope. These include light-headedness; nausea; sensations of flushing; tingling or numbness of the arms or legs; anxiety; visual disturbance; or a feeling they are about to faint.

† Presyncope refers to the premonitory symptoms of impending collapse 1. Seddon P. Harness suspension: review and evaluation of existing information CRR 451/2002, HSE Books, HMSO, Norwich; 2002.

The term “suspension trauma” is one, which has developed as parlance amongst many who work in the fall protection industry and training sector. In an earlier Health and Safety Executive (HSE) report1 and a number of published articles, suspension trauma was used to describe the situation of a person falling into suspension on a rope and then becoming unconscious. In this scenario the loss of consciousness is not due to any physical injury but rather it is thought that orthostasis, motionless vertical suspension, is responsible. “Trauma” is therefore an inappropriate epithet, which may be better replaced by the descriptive term “syncope”.

Syncope is the sudden transient loss of consciousness and postural tone with spontaneous recovery2. The causes of syncope can be classified as vascular: resulting from changes to blood vessels or their reflex responses, cardiac: relating to structural abnormalities of the heart or to changes in its rhythm, neurological: conditions such as migraine or seizures, metabolic: due to ingested or other toxicants e.g. drugs or alcohol and including abnormalities of biochemistry, psychogenic: anxiety, panic and somatisation disorders, and finally, syncope of unknown origin.

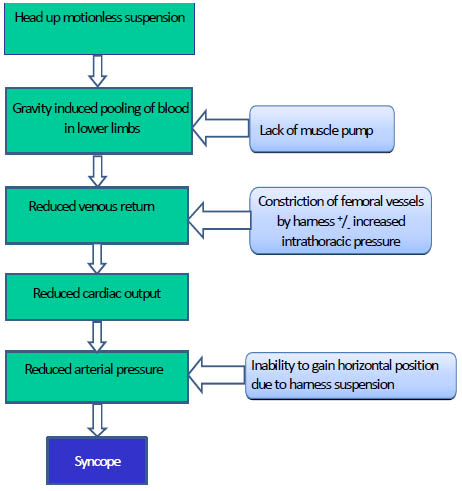

Syncope occurring with vertical suspension is principally related to the motionless state (Figure 1) and can be induced by use of a cardiac tilt table in which the subject rests in the upright position with their back against a board with support from a bicycle type seat but without a foot rest. Pooling of blood in the gravitationally dependent legs leads to the clinical state described as orthostasis. After prolonged vertical tilt most subjects will become symptomatic. This may produce symptoms such as light-headedness; nausea; sensations of flushing; tingling or numbness of the arms or legs; anxiety; visual disturbance; or faintness. This state is often referred to, as “presyncope” i.e. if some postural or physiological correction does not take place syncope will consequentially follow. In suspension with some types of chest harness the discomfort caused may lead to increased pressure within the chest cavity further reducing venous blood return. Normally, on standing, 500 to 800 ml of blood is displaced to the abdomen and legs causing physiological consequences on cardiac output, blood vessel tone and reflex responses, which should maintain stable blood pressure. A drop within 3 minutes of standing of 20mmHg in systolic blood pressure or 10mmHg diastolic blood pressure is defined as postural hypotension. Some people are more likely to suffer this condition than others and some circumstances such as dehydration, alcohol and prescribed medication can affect an individual predisposition2.

The term “suspension syncope” or indeed “suspension presyncope” does not therefore assume that any one pathological mechanism is responsible for the loss of consciousness or symptoms occurring in suspension and acknowledges that multiple factors may operate. Experimental evidence and clinical experience point to suspension orthostasis as being the most common circumstance likely to induce syncope in otherwise fit and healthy subjects. The published literature was reviewed to establish if there was a need to change the current first aid guidelines. The literature reviewed fails to document cases occurring during industrial use of fall protection. Seddon1 states that in response to a request to a questionnaire placed on the Industrial Rope Access Trade Association website for 6 months with periodic reminders, he had no reports of presyncope or syncope. The only casualties he became aware of from direct enquiries were cases occurring during rescue training when subjects were deliberately suspended and motionless.

Figure 1 - The Mechanism of Suspension Syncope

The medical complications arising from suspension in harnesses were highlighted by a 1972 conference of Mountain Rescue Doctors in Innsbruck3. One of the conference papers proposed, “…. we therefore take the view that a person cut free from the rope should only sit or lean against the rock, but not lie down in order to prevent the blood returning too quickly to the right atrium”4. This paper which has not been published in the peer reviewed medical literature gave an opinion on management and a hypothesis to support the proposal but provided no experimental evidence to indicate any benefit. The authors lay their own test subjects in a supine position. The assertion of the need to prevent a supine posture following rescue from suspension was repeated by Damisch and Schauer5 in 1985 with a footnote to their work conducted at Innsbruck examining a series of harnesses and also by Petermeyer and Unterhalt6 in 1997. Although these authors reiterated the advice given by Flora et al, no evidence of benefit was presented to support the hypothesis. Seddon’s review (2001) repeated and referenced this advice, however other authors and advisers may have promulgated the considerations for rescue and treatment mentioned without their own critical assessment of the primary research. The present work provides a critical review of the medical evidence for the management of suspension syncope using widely accepted methodology for evidence appraisal.

2.1 EVIDENCE BASED REVIEW METHOD

The project team agreed that the best method of forming authoritative advice would be to undertake an evidence-based review of the medical literature. Clinical practice guidelines are “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances". Their purpose is "to make explicit recommendations with a definite intent to influence what clinicians do" 7.

A guideline development group was formed which consisted of the guideline leader, project manager, guideline co-ordinator and two member / appraisers (Figure 2). The Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) methodology7 was the framework for the development of the guideline. A set of four questions was formulated between the guideline development group and the HSE customer. The Population Intervention Comparison Outcome (PICO) format was utilised to address the information requirements (Figures 3 & 4). Following the completion of the evidencebased review and compiling of the draft report, a meeting of relevant stakeholders was held at the Health and Safety Laboratory to discuss the circumstances of harness suspension, the review methodology and the initial recommendations formulated from the work undertaken. Feedback was actively sought from the invited stakeholders and taken into account in the production of the final report.

2.1.1 Figure 2 – Guideline Development Group

Guideline Leader

Dr Anil Adisesh

Deputy Chief Medical Officer, Centre for Workplace Health,

Health and Safety Laboratory, Buxton, UK

Guideline Co-ordinator

Jacqui Foxlow

Occupational Health Nurse, Centre for Workplace Health,

Health and Safety Laboratory, Buxton, UK

Project Manager

Alison Codling

Senior Occupational Health Nurse, Centre for Workplace Health,

Health and Safety Laboratory, Buxton, UK

Member/Appraisers

Dr Caroline Lee, Specialist Registrar in Emergency Medicine,

Academic Department of Clinical Traumatology, University of Birmingham, UK

Prof. Keith Porter, Professor of Clinical Traumatology,

Academic Department of Clinical Traumatology, University of Birmingham, UK

2.1.2 Figure 3 – Key Questions

Q.1 What circumstances can cause suspension trauma?

Q.2 How common is suspension trauma?

Q.3 What first aid should be applied to a known case of suspension trauma?

Q.4 How is suspension trauma recognised clinically?

2.1.3 Figure 4 – Key Questions Organised into PICO Format

| POPULATION | INTERVENTION | COMPARISON | OUTCOME | |

| Q1 | Anyone suspended & developing suspension trauma | Suspension | Anyone suspended & not developing suspension trauma | Risk Factors |

| Q2 | Anyone suspended & developing suspension trauma | Suspension | Anyone suspended & not developing suspension trauma | Prevalence |

| Q3.1 | Anyone suspended & conscious with any signs and symptoms | Suspension | Anyone suspended & conscious with any signs and symptoms of suspension trauma | Appropriate first aid following conscious suspension |

| Q3.2 | Anyone suspended & unconscious | Suspension | Anyone suspended & unconscious with signs and symptoms of suspension trauma | Appropriate first aid following unconscious suspension |

| Q4 | Anyone suspended with any signs & symptoms | Suspension | Anyone suspended with signs & symptoms of suspension trauma | Differentiation of suspension trauma signs and symptoms |

A list of relevant key words to be used in a literature search was agreed. Information scientists from the Health and Safety Executive’s Knowledge Centre performed a literature search. Abstracts were reviewed and papers selected for critical appraisal.

2.2.1 Databases Interrogated

The search was run on:

Medline coverage 1951 to present

Embase coverage 1974 to present

CISDOC 1987 to present

Hseline 1987 to present

Nioshtic and Nioshtic 2 1977 to present

OSHline 1998 to present

Rilosh 1975 to present

Healsafe 1981 to present

ROSPA 1980 to present

The search returned a number of abstracts related to the hypotensive effects of medication and other medical causes of orthostatic hypotension these articles were deselected at initial screening as were other obviously non-relevant subjects.

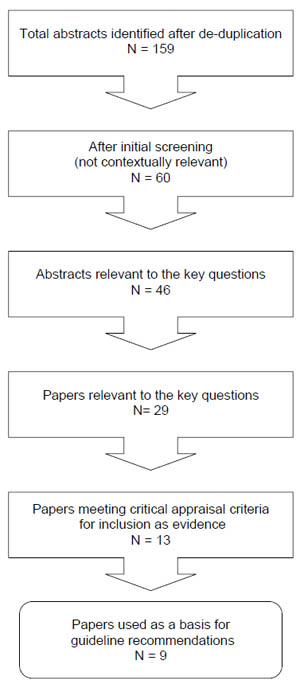

The search strategy is detailed in Figure 5 with the numbers of articles returned at each step. The flow of articles through the evidence review is enumerated in the subsequent flow chart (Figure 6).

2.2.2 Figure 5 - Search Strategy

| Search Step | Search Term | Total |

| 1 | SUSPENSION NEAR TRAUMA | 27 |

| 2 | SUSPENSION NEAR ( MEDICAL ADJ EFFECT$1) | 0 |

| 3 | SUSPENSION NEAR (PHYSIOLOGICAL ADJ EFFECT$1) | 12 |

| 4 | SUSPENSION NEAR UNCONSCIOUS$4 | 5 |

| 5 | SUSPENSION NEAR SYNCOPE | 0 |

| 6 | SUSPENSION NEAR PRESYNCOPE | 0 |

| 7 | (SUSPENSION NEAR MEDICAL or SUSPENSION NEAR PHYSIOLOGICAL) and (HARNESS$3 OR PARACHUTES$4 OR MOUNTAIN$7 OR CLIMB$3 OR CAVE$3 OR SPELEOLOG$4 OR ROPE OR ROPES) | 7 |

| 8 | (SUSPENSION NEAR MEDICAL or SUSPENSION NEAR PHYSIOLOGICAL) and (FALL OR FALLS OR FALLING OR FELL) | 8 |

| 9 | Search steps 1 to 8 limited to human tag (Medline and Embase only) | 17 |

| 10 | RESCUE ADJ DEATH | 28 |

| 11 | HARNESS$3 NEAR (INDUCED NEAR PATHOLOG$3) | 6 |

| 12 | HARNESS$3 NEAR (MEDICAL NEAR EFFECT$1) | 3 |

| 13 | HARNESS$3 NEAR (PHYSIOLOGICAL NEAR EFFECT$1) | 0 |

| 14 | HARNESS$3 NEAR UNCONSCIOUS$4 | 3 |

| 15 | HARNESS$3 NEAR SYNCOPE | 0 |

| 16 | HARNESS$3 NEAR PRESYNCOPE | 0 |

| 17 | Search steps 11 to 16 limited to human tag (Medline and Embase only) | 21 |

| 18 | ORTHOSTATIC NEAR SHOCK | 36 |

| 19 | ORTHOSTATIC NEAR HYPOTENSION | 15861 |

| 20 | ORTHOSTATIC NEAR INTOLERANCE | 1171 |

| 21 | ORTHOSTATIC NEAR SYNCOPE | 497 |

| 22 | ORTHOSTATIC NEAR PRESYNCOPE | 72 |

| 23 | ORTHOSTATIC NEAR SYNDROME | 702 |

| 24 | Search steps 18 to 23 and SUSPENSION | 77 |

| 25 | Search steps 18 to 23 and (HARNESS$3 OR PARACHUTES$4 OR MOUNTAIN$7 OR CLIMB$3 OR CAVE$3 OR SPELEOLOG$4 OR ROPE OR ROPES) | 44 |

| 26 | Search steps 18 to 23 and (FALL OR FALLS OR FALLING OR FELL) in title or descriptors | 474 |

| 27 | Search steps 24 to and 26 limited human tag (Medline and Embase only) | 525 |

| 28 | Not drug in title or descriptor (medline only) | 112 |

| 29 | Search step 27 And harness$3 (medline only) | 10 |

| 30 | 274 (HEAD ADJ UP ADJ TILT) NEAR SYNCOPE | 541 |

| 31 | (HEAD ADJ UP ADJ TILT) NEAR PRESYNCOPE | 38 |

| 32 | ((VASO ADJ VAGAL) OR VASOVEGAL) NEAR SYNCOPE | 78 |

| 33 | ((VASO ADJ VAGAL) OR VASOVEGAL) NEAR (PRESYNCOPE) | 0 |

| 34 | VENOUS NEAR POOLING NEAR SYNCOPE | 15 |

| 35 | VENOUS NEAR POOLING NEAR PRESYNCOPE | 0 |

| 36 | Search steps 30 to 35 and SUSPENSION | 1 |

| 37 | Search steps 30 to 35 and (HARNESS$3 OR PARACHUTES$4 OR MOUNTAIN$7 OR CLIMB$3 OR CAVE$3 OR SPELEOLOG$4 OR ROPE OR ROPES) | 0 |

| 38 | Search steps 30 to 35 and (FALL OR FALLS OR FALLING OR FELL) in title or descriptor | 4 |

| 39 | Steps 36 to 38 Limit human tag (medline and Embase only) | 5 |

| 40 | Step 39 And harness$3 (medline and Embase only) | 0 |

| Note: near means within 5 words, $3 means 3 letter truncation. There was no language restriction. |

||

2.2.3 Figure 6 - Flow Chart for Study Selection

2.3 CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF PAPERS

The selected papers were assessed for methodological quality, using a proforma adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Appendix 1). The SIGN grading system was used to grade the levels of evidence offered by each paper reviewed and the recommendations made by the appraisers. Considered judgement forms were completed so that the basis for the recommendations could be understood more clearly.

Appraisers were also asked to identify any follow-on papers listed in the references of the papers they were appraising.

A stakeholders’ workshop was convened on the 30 April 2008 to discuss the draft evidence based review report produced by the Health and Safety Laboratory on behalf of the Health and Safety Executive.

Stakeholders from industrial training organisations and professional bodies concerned with fall arrest and rope access, union representatives, medical researchers and advisers, rescue services including the ambulance service and sport organisations, and colleagues from the Health and Safety Executive were invited to attend (Appendix 4). The guideline development group and colleagues from the Engineering Safety Unit at the Health and Safety Laboratory gave presentations about the background to the review, harnesses for fall protection, medical aspects of orthostasis, the SIGN methodology (figure 7) and the evidence review with draft recommendations. The discussion within the workshop and subsequent information provided by attendees was most helpful in further developing the final report. It is hoped that this process of engagement of the participants will assist with acceptance and dissemination of the recommendations.

2.4.1 Figure 7 - SIGN Evidence and Recommendation Grading System

Levels of Evidence| 1++ | High quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), or RCTs with a very low risk of bias |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a low risk of bias |

| 1– | Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a high risk of bias |

| 2++ | High quality systematic reviews of case-control or cohort studies High quality case-control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding, bias, or chance and a high probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2+ | Well conducted case-control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding, bias, or chance and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2– | Case-control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding, bias, or chance and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal |

| 3 | Non-analytic studies, e.g. case reports, case series |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

Grades of recommendation

| A | At least one meta-analysis, systematic review, or RCT rated as 1++, and directly applicable to the target population; or A systematic review of RCTs or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+, directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results |

| B | A body of evidence including studies rated as 2++, directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 1++ or 1+ |

| C | A body of evidence including studies rated as 2+, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2++ |

| D | Evidence level 3 or 4; or Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+ |

Good Practice Points

| GPP | Recommended best practice based on the clinical experience of the guideline development group |

3 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This section includes the full recommendations for the first aid management of harness suspension and answers the PICO format questions that were framed. The presentation of the evidence is summarised in the considered judgement forms used for each question with the recommendations, which follow.

The individual studies used as evidence and the critical appraisal of this evidence is presented in Appendix 2.

After the completion of the evidence review there was a publication of high quality research conducted by researchers at the United States, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) concerning the development of a prototype harness accessory designed to deploy passively, allowing the legs to assume a bent knee posture when in suspension8. Although this study was not included in the evidence review, it confirms the finding of the elevated leg semi recumbent suspension position being better tolerated as reported by Madsen et al 9. The authors also comment in respect of harness suspension in chest and back suspension without this posture that, “to ensure that no more than 5% of workers would experience symptoms [of suspension presyncope or syncope], rescue would have to occur in 7 minutes for a chest attachment point and in 11 minutes for a back attachment point”. In this study the elevated leg semi recumbent suspension position was tolerated for a mean of 58 minutes with all withdrawals being due to discomfort rather than medical symptoms or signs8.

3.1 LIST OF EVIDENCE BASED RECOMMENDATIONS

| SIGN Grade | |

| Fall arrest systems incorporating a harness should be a last measure since the means for recovery from a fall into suspension may exceed the time to presyncope, which may then be followed by syncope in a time period which is unpredictable. | B |

| In head up suspension, elevation of the legs may prolong tolerance. | B |

| No change should be made to the standard UK first aid guidance for the post rescue recovery of a semi-conscious or unconscious person in a horizontal position, even if the subject of prior harness suspension. | B |

| No change should be made to the standard UK first aid guidance of ABC management, even if the subject of prior harness suspension. | B |

| A casualty who is experiencing pre-syncopal symptoms or who is unconscious whilst suspended in a harness, should be rescued as soon as is safely possible. | B |

| If the rescuer is unable to immediately release a conscious casualty from a suspended position, elevation of the legs by the casualty or rescuers where safely possible may prolong tolerance of suspension. | B |

| First responders to persons in harness suspension should be able to recognise the symptoms of pre-syncope. These include light-headedness; nausea; sensations of flushing; tingling or numbness of the arms or legs; anxiety; visual disturbance; or a feeling they are about to faint. | B |

| Head down suspension should be treated with as much urgency as head up suspension. | D |

| Methods of collating data on non-fatal and fatal falls in all personal fall protection systems where there is a risk of suspension in a harness should be explored together with the availability of data, as a denominator on the number of hours of fall protection used. | D |

| Post mortem examinations on fatalities after falls into rope suspension should specifically look for hypothesised features of ‘suspension trauma’ to establish whether there is any existence of this clinical entity. | D |

| Supplementary oxygen, if available, should be administered to any person who has suffered syncope during harness suspension. | GPP |

| Consider removing a harness suspended person from suspension in the direction of gravity i.e. downwards, so as to avoid further negative hydrostatic force, however this measure should not otherwise delay rescue. | GPP |

| An emergency 999 ambulance or equivalent qualified paramedical or medical provider should be called for anyone who becomes unconscious in harness suspension whether apparently recovered or not. | GPP |

3.2 CONSIDERED JUDGEMENT FORMS

| Considered Judgement Forms - Key question 1: What circumstances can cause suspension trauma? |

| 1. Volume of evidence Comment here on any issues concerning the quantity of evidence available on this topic and its methodological quality. |

| All the studies reviewed, including those not meeting criteria for inclusion as evidence, have investigated the effect of motionless head up suspension in various harnesses or using a tilt table. The effect of lower limb movement in suspension does not appear to have been formally assessed. Only one paper accepted as evidence reports the effects of inverse (head down) suspension and then in the context of post mortem findings. |

| 2. Applicability Comment here on the extent to which the evidence is directly applicable to UK practice |

| The experimental circumstances reported are expected to be analogous to those seen in industrial rope access where the subject has been in motionless suspension. |

| 3. Generalisability Comment here on how reasonable it is to generalise from the results of the studies used as evidence to the target population for this guideline. |

| In the experimental situations subjects were raised to suspension whereas in harnessbased personal fall protection systems, it is expected that victims will unexpectedly fall into suspension. The physiology of the latter situation may differ significantly but it is not clear whether this would usually delay or enhance the effects of orthostasis. The research available does allow inference of the effects solely of orthostasis. |

| 4. Consistency Comment here on the degree of consistency demonstrated by the available of evidence. Where there are conflicting results, indicate how the group formed a judgement as to the overall direction of the evidence |

| There is high consistency of the reported findings in motionless suspension both in symptoms described and the effects of harness type. |

| 5. Clinical impact Comment here on the potential clinical impact that the intervention in question might have - e.g. size of patient population; magnitude of effect; relative benefit over other management options; resource implications; balance of risk and benefit. |

| N/A |

| 6. Other factors Indicate here any other factors that you took into account when assessing the evidence base. |

| N/A |

| Evidence statement | Grade |

| Motionless head up suspension leads to syncope. Madsen P et al 1998, Mallard M 1990, Orzech M A et al 1987. | 1+ |

| Head up suspension in mountaineering or caving has lead to fatalities. Flora G, Holzl HR 1972, Patscheider H 1972, Fodisch J 1972, Mallard M 1990. | 3 |

| The duration of suspension may be determined by anthropometric values for some body harnesses. Weber P, Michela-Brundel G 1997. | 1+ |

| Motionless head up suspension leads to presyncope in most normal subjects within 1 hour and in a fifth within 10 minutes. Madsen P et al 1998. | 1+ |

| There is a near linear relationship between head up tilt and time to presyncope in normal subjects. Madsen P et al 1998. | 1+ |

| Recommendation | Grade |

| Fall arrest systems incorporating a harness should be a last measure since the means for recovery from a fall into suspension may exceed the time to presyncope, which may then be followed by syncope in a time period which is unpredictable. | B |

| Evidence statement | Grade |

| Head up suspension with elevated legs is better tolerated than with legs dependent. Madsen P et al 1998. | 1+ |

| Recommendation | |

| In head up suspension elevation of the legs may prolong tolerance. | B |

| Evidence statement | Grade |

| Head down suspension has been fatal in some circumstances but may take longer to cause loss of consciousness. Madea B 1993. | 3 |

| Recommendation | |

| Head down suspension should be treated with as much urgency as head up suspension. | D |

| Considered Judgement Forms - Key question 2: How common is suspension trauma? |

| 1. Volume of evidence Comment here on any issues concerning the quantity of evidence available on this topic and its methodological quality. |

| No systematic studies of the incidence of suspension trauma or falls into rope protection were found. Flora and Holzl report 23 falls in 17 years from the Austrian Alps. 10 (43%) of these were fatal but information bias is likely with a more complete ascertainment of fatal than non-fatal falls. Seddon comments in his 2002 review that he had no reports of symptoms relating to suspension trauma despite a widely distributed request in the UK. |

| 2. Applicability Comment here on the extent to which the evidence is directly applicable to UK practice |

| The incidence is unlikely to be relevant to industrial rope access and even mountaineering conditions in the UK will differ from Austria although the potential for falling into suspension exists. |

| 3. Generalisability Comment here on how reasonable it is to generalise from the results of the studies used as evidence to the target population for this guideline. |

| The type of harness Flora and Holzl refer to is a simple rope around the chest and has specific problems associated with its use. The harness is not typical of those used for harness-based personal fall protection systems or in modern-day climbing and caving. However motionless orthostatic suspension would have complications independent of harness design. |

| 4. Consistency Comment here on the degree of consistency demonstrated by the available of evidence. Where there are conflicting results, indicate how the group formed a judgement as to the overall direction of the evidence |

| N/A |

| 5. Clinical impact Comment here on the potential clinical impact that the intervention in question might have - e.g. size of patient population; magnitude of effect; relative benefit over other management options; resource implications; balance of risk and benefit. |

| N/A |

| 6. Other factors Indicate here any other factors that you took into account when assessing the evidence base. |

| N/A |

| Evidence statement | Grade |

| There is no evidence reporting the incidence of suspension trauma in industrial fall prevention. | |

| Recommendation | Grade |

Methods of collating data on non-fatal and fatal falls in all personal fall protection systems where there is a risk of suspension in a harness should be explored together with the availability of data, as a denominator on the number of hours of fall protection used. |

GPP |

Post mortem examinations on fatalities after falls into rope suspension should specifically look for hypothesised features of ‘suspension trauma’ to establish whether there is any existence of this clinical entity. |

GPP |

| Considered Judgement Forms - Key question 3: What first aid should be applied to a known case of suspension trauma? |

| 1. Volume of evidence Comment here on any issues concerning the quantity of evidence available on this topic and its methodological quality. |

| There are no studies that have been designed to answer this question. In a number of harness suspension studies subjects experienced presyncope and even in some cases syncope. All subjects were successfully recovered by lying supine. Several authors give opinions about an alternative recovery position but in none of the studies were subjects recovered in the semirecumbent way later suggested. There is no evidence of so-called “reflow syndrome” or reperfusion injury being reported in suspension orthostasis. |

| 2. Applicability Comment here on the extent to which the evidence is directly applicable to UK practice |

| N/A |

| 3. Generalisability Comment here on how reasonable it is to generalise from the results of the studies used as evidence to the target population for this guideline. |

| Only anecdotal evidence suggests that the standard first aid may have any adverse effect. |

| 4. Consistency Comment here on the degree of consistency demonstrated by the available of evidence. Where there are conflicting results, indicate how the group formed a judgement as to the overall direction of the evidence |

| In all studies recovery of symptomatic subjects was undertaken supine. |

| 5. Clinical impact Comment here on the potential clinical impact that the intervention in question might have - e.g. size of patient population; magnitude of effect; relative benefit over other management options; resource implications; balance of risk and benefit. |

| To change the recommendation for first aid recovery of a semi-conscious or unconscious person in specific circumstances may be confusing for first aiders and lead to inappropriate measures for other victims, which could potentially be fatal. To recommend a change in current first aid practice even for the specific circumstance of suspension trauma it must be shown that the risk of change is outweighed by the benefit. Since there are no reported cases of industrial suspension orthostasis the most likely circumstances of semi-conscious or unconscious victims that a first aider will be confronted with, will be from other causes even in a construction workplace and they must be clear about the prompt action required. It is also possible that in some cases of semiconscious or unconscious victims suspended on a rope, that the cause of their comatose state is due to other physical injury and that to fail to put them in a horizontal position may be deleterious. |

| 6. Other factors Indicate here any other factors that you took into account when assessing the evidence base. |

| None |

| Evidence statement | Grade |

| All study subjects recovered from suspension or head up tilt presyncope, uneventfully after being placed quickly into the supine position. Orzech M A et al 1987, Madsen P et al 1998, Mallard M 1990. | 1+ |

| One case of syncope with bradycardia during lowering from suspension recovered quickly without any medically adverse effects when placed in the supine position. Other cases of syncope without bradycardia subjectively completely normalised after a few minutes in the horizontal position. Orzech M A et al 1987. | 1+ |

| Recommendation | Grade |

| No changes should be made to the standard UK first aid guidance for the post rescue recovery of a semi-conscious or unconscious person in a horizontal position, even if the subject of prior harness suspension. | B |

| No changes should be made to the standard UK first aid guidance of ABC management, even if the subject of prior harness suspension. | B |

| An emergency 999 ambulance or equivalent qualified paramedical or medical provider should be called for anyone who becomes unconscious in harness suspension whether apparently recovered or not. | GPP |

| Evidence statement | Grade |

| Head up suspension with elevated legs is better tolerated than with legs dependent. Madsen P et al 1998. | |

| Recommendation | 1+ |

| If the rescuer is unable to immediately release a conscious casualty from a suspended position, elevation of the legs by the casualty or rescuers where safely possible may prolong tolerance of suspension. | B |

| Evidence statement | Grade |

| Motionless head up suspension leads to presyncope in most normal subjects within 1 hour and in a fifth within 10 minutes. Madsen P et al 1998. | 1+ |

| There is a near linear relationship between head up tilt and time to presyncope in normal subjects. Madsen P et al 1998. | 1+ |

| If harness suspension is prolonged after the onset of syncope irreversible hypoxia and death may result. Flora G, Holzl HR 1972, Patscheider H 1972, Fodisch J 1972, Mallard M 1990. | 3 |

| Recommendation | Grade |

| A casualty who is experiencing pre-syncopal symptoms or who is unconscious whilst suspended in a harness, should be rescued as soon as is safely possible. | B |

| Supplementary oxygen, if available, should be administered to any person who has suffered syncope during harness suspension. | GPP |

| Consider removing a harness suspended person from suspension in the direction of gravity i.e. downwards, so as to avoid further negative hydrostatic force, however this measure should not otherwise delay rescue. | GPP |

| Considered Judgement Forms - Key question 4: How is suspension trauma recognised clinically? |

| 1. Volume of evidence Comment here on any issues concerning the quantity of evidence available on this topic and its methodological quality. |

| Many harness suspension studies have enquired about the symptoms experienced by volunteer subjects in suspension. These symptoms that occur prior to the onset of syncope are termed presyncope and have been well characterised. The onset of syncope itself was not deliberately studied in any of the works reviewed although some episodes of syncope were reported. Most studies have also used the onset of systolic hypotension <90mmHg or bradycardia as medical withdrawal criteria. |

| 2. Applicability Comment here on the extent to which the evidence is directly applicable to UK practice |

| Directly applicable to UK practice. |

| 3. Generalisability Comment here on how reasonable it is to generalise from the results of the studies used as evidence to the target population for this guideline. |

| The symptoms experienced in volunteer studies are expected to be the same as those that would occur in motionless harness suspension excluding the effects of any fall or other injury. |

| 4. Consistency Comment here on the degree of consistency demonstrated by the available of evidence. Where there are conflicting results, indicate how the group formed a judgement as to the overall direction of the evidence |

| There is a high level of consistency between studies in the presyncope symptoms sought and reported. |

| 5. Clinical impact Comment here on the potential clinical impact that the intervention in question might have - e.g. size of patient population; magnitude of effect; relative benefit over other management options; resource implications; balance of risk and benefit. |

| Those persons including first responders to harness suspension will be able to recognise the symptoms of presyncope and therefore impending syncope. |

| 6. Other factors Indicate here any other factors that you took into account when assessing the evidence base. |

| None |

| Evidence statement | Grade |

| Study subjects in harness suspension most often reported light headedness, nausea, sensation of flushing, tingling and/or numbness of arms/legs, drowsiness in decreasing order of frequency with visual disturbance and anxiety in single cases. Orzech M A et al 1987, Weber P, Michela-Brundel G 1997, Mallard M 1990. |

1+ |

| Subjects with presyncope may have one or more symptoms. Orzech M A et al 1987, Weber P, Michela-Brundel G 1997, Mallard M 1990. |

1+ |

| Recommendation | Grade |

| First responders to persons in harness suspension should be able to recognise the symptoms of pre-syncope. These include light-headedness; nausea; sensations of flushing; tingling or numbness of the arms or legs; anxiety; visual disturbance; or a feeling they are about to faint. | B |

As a result of the literature review and appraisal, areas were identified which may benefit from further study and these are listed below for other researchers and stakeholders in this field to consider addressing:

- Does lower limb activity affect the duration of tolerated harness suspension?

Although it has been often said that activity of the lower limbs in suspension is protective against suspension syncope, no trials were found that formally addressed this question.

- What is the physiological effect of an unexpected drop into harness suspension?

All the trials retrieved either raised subjects into suspension or used cardiac tilt table testing. Whilst this may be a useful simulation of harness suspension, a more realistic test might use a drop at least to determine if there is any difference between these situations.

- What is the predictive value of anthropometric data on head up tilt and suspension tolerance?

Further knowledge of the effect of these anthropometric data may aid future harness design and methods of aiding tolerance of suspension.

- What standard format should be used for recording a fall event?

A standard recording format for a fall event would aid comparison of information gathered from different workplaces or fall scenarios. The aggregation of such information may be used for both preventive purposes and reporting to the health care responders e.g. ambulance services.

- When fall protection is used how often do workers fall into suspension and what symptoms are experienced?

The collation of such data would inform the need for further preventive measures and the incidence of suspension syncope or presyncope.

- What is the effect of the semi-recumbent bent knee posture on recovery from orthostatic presyncope?

Whilst there is limited evidence that suspension in a semi-recumbent bent knee posture is better tolerated, there is no evidence to support assertions that post rescue this position is physiologically superior or even equivalent to the horizontal position recommended in UK first aid guidance. This question could be addressed quite readily through appropriate human studies.

- Do any toxic metabolites accrue during orthostasis that may be likely to have adverse physiologic effects?

One of the putative pathophysiologic mechanisms that led some authors to advise against lying victims of suspension syncope horizontal was that toxic metabolites would re-enter the circulation and cause adverse effects. Investigation of whether such metabolites accrue and their concentration, would be a first step towards evaluating whether any adverse effects from prolonged suspension may be envisaged with horizontal positioning.

- What is the time interval between the onset of presyncope symptoms and syncope in orthostasis?

Knowledge of factors that may aid the prediction of incipient syncope would be helpful for first responders to cases of harness suspension.

- Suggested Audit Criteria:

| Priority topic | Criteria |

| First aid at work trainers should be aware of the appropriate action for a post rescue suspension casualty. | % of first aid at work providers training to the evidence based guidance. |

| First aiders should be aware of the appropriate action for a post rescue suspension casualty. | % of first aiders aware of the evidence based guidance. |

| First aiders should be able to recognise the symptoms of pre-syncope. | % of first aiders aware of the symptoms of pre-syncope. |

5.1 APPENDIX 1 - CRITICAL APPRAISAL FORM

Reviewer(s):

Author, title:

Study type (tick all that apply)

Randomised controlled trial

Systematic review

Meta-analysis

Qualitative research

Literature review

Case-control study

Longitudinal/cohort study

Other

(Please describe)

Initial comments:

SCREENING QUESTIONS

1. Does the paper have a clearly focused aim or research question?

| Yes | No | Can't tell |

Consider:

1. population studied

2. interventions delivered

3. outcomes

2. Is the chosen method appropriate?

| Yes | No | Can't tell |

Consider whether:

1. the authors explain their research design

2. the chosen method address the research question

Is it worth continuing?

| Yes | No |

Please explain

Detailed questions

3. Has the research been conducted rigorously?

| Yes | No | Can't tell |

Consider:

1. search strategy described

2. inclusions and exclusions

3. more than one researcher

4. resolving issues of bias

4. Is it clear how data has been analysed?

| Yes | No | Can't tell |

Consider:

1. were study results combined

2. if so was this reasonable

3. in-depth description of the analysis process

4. all participants accounted for

5. contradictory findings explained

5. Is there a clear statement of findings?

| Yes | No | Can't tell |

Consider:

1. sufficient evidence to support conclusions

2. do findings support the research question

3. precision of results

4. all important variables considered

6. How are the results presented?

Consider:

1. are the results presented numerically, i.e. p-value, OR (odds ratio)

2. are the results presented narratively

7. What is the main result?

Consider:

1. how large is the size of the result

2. how meaningful is the result

3. how would you sum up the bottom-line result in one sentence

8. Are there limitations to the research?

| Yes | No | Can't tell |

Consider:

1. was the sample size large enough

2. were all important outcomes considered

3. was the intervention process adequately described

4. was there any follow-up data

5. do the authors acknowledge weaknesses

9. Can the results be applied to a UK context?

Accept for inclusion as evidence

| Yes | No | Can't tell |

Refer to guideline leader

| Yes | No |

Guideline leader’s notes:

Any references that need to be followed up from this article?

5.2 APPENDIX 2 - EVIDENCE TABLES

5.3 APPENDIX 3 - GLOSSARY OF TERMS

Bradycardia: Abnormally slow heart rate or pulse.

Hypotensive/Hypotension: Abnormal lowering of the blood pressure.

Hypoxia: A diminished amount of oxygen to the tissues : The sensation of feeling sick.

Nausea: The sensation of feeling sick.

Orthostatic: Relating to or caused by erect posture.

Orthostatic Hypotension: Also known as postural hypotension, and, colloquially, as head rush or a dizzy spell, is a form of hypotension, which there is a sudden (less than 3 minutes) fall in blood pressure that occurs when a person assumes a standing position usually after a prolonged period of rest.

Pre Syncope: Symptoms and signs, which are indicative of impending collapse.

Reflow Syndrome: A putative state said to be caused when stagnant pooled blood in the legs is allowed to rapidly flow back into the circulation.

Semi-Recumbent: Lying on the back at a 45o angle.

Supine: Lying horizontally on the back with the face upwards.

Suspension: The state of being suspended; something on or by which something else is suspended or hung; something that is suspended or hung.

Syncope: The sudden transient loss of consciousness and postural tone with spontaneous recovery as may occur with a simple faint.

Trauma: A body wound or shock produced by sudden physical injury, as from violence or accident.

Unconscious: Without awareness, sensation, or cognition. This may vary in depth from deeply unconscious where no response can be obtained to a level of consciousness where the individual can be roused by speech or non-painful stimuli.

Vasovagal: Relating to or involving blood vessels and the vagus nerve.

5.4 APPENDIX 4 - STAKEHOLDER WORKSHOP SUMMARY AND SATKEHOLDER LIST

Review of the Current Guidance and Advice Available on First Aid Measures for Dealing with Suspension Trauma Casualties

Stakeholders Workshop 30.04.08

There were 42 attendees including the presenters, at the stakeholder’s workshop convened to discuss the draft evidence based review report produced by the Health and Safety Laboratory on behalf of the Health and Safety Executive.

Louise Robinson, Professor Keith Porter and Anil Adisesh gave presentations before the draft recommendations were reviewed in the afternoon session. Anil Adisesh gave an overview of the review background and methodology. The purpose of the review was to produce, “Simple, clear, agreed and authoritative recommendations for first aid for those who may be suffering from suspension trauma, using fall arrest systems in the workplace”. The use of the term “suspension trauma” might itself be questioned since whilst suspension is a necessary condition, trauma is not an accurate description of the possible ensuing medical circumstances.

Louise Robinson’s presentation on harnesses for fall protection concluded that suspension in a fall arrest harness at work was unintentional. It was intentional with industrial sit harnesses. Both situations were applicable to sport climbing harnesses. An overview was given of fall arrest systems, which are used where it is not practical to fit any permanent means of fall prevention. The user’s position of suspension in front and rear attachment harnesses was illustrated and examples of harnesses were displayed. The use of industrial sit harnesses for rope access was then presented with illustrations of the suspension position for an unconscious subject. It was however noted that the “cow’s tail” back up would limit the fall to about 1 metre and hence also limit consequent injury. Falls in sport climbing were more likely to be of greater distance since there is a dependency on the protection used and the skill of the belayer. Rescue of casualties was discussed with the options of remote rescue, rescue in descent and self-evacuation. Lowering a casualty is generally preferable since this is a less demanding manual handling task.

Professor Keith Porter described the medical condition of orthostasis and the attendant complications. Reference was made to previous models explaining the course of uncorrected orthostasis and a simplified diagram was presented. Some other medical conditions and treatments are associated with orthostatic changes. The range of diagnoses was discussed. Rescue of casualties from water is a different medical situation from hanging suspension since there are the physiological effects of the loss of external hydrostatic pressure and thermal effects to consider. Some authors have failed to recognise these differences. Elevation of the legs when in hanging suspension is better tolerated than with the legs dependent. This was a finding from the review of recent research but had previously been the subject of conjecture. The inability to exercise the legs against a fixed point was considered to be contributory to collapse with potentially fatal consequences.

There followed interaction with the workshop in clarifying various questions.

Do harnesses reduce venous return?

Do harnesses produce a tourniquet effect?

Is there a significant reperfusion effect?

What happens in parachutists?

Anil Adisesh then outlined the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) methodology that was used to perform the review. This is a structured method of formulating a question and then gathering evidence to address the question with critical appraisal of the literature.

The second session discussed each of the 4 questions raised by the review and the draft recommendations. Helpful points were made during this discussion period about correct technical terminology for fall prevention, time to rescue, use of alternative terms for “suspension trauma”, and gathering intelligence on falls from height. Other questions and discussion addressed the issue of first aid response and whether this applied to non-work situations. It was clarified that the work was undertaken with a focus on the workplace and other organisations may wish to take account of it in developing their own guidelines and practice.

A point of discussion but also broad agreement amongst the clinical professionals present was that, “no changes to the standard UK first aid guidance for the recovery of a semiconscious or unconscious person in a horizontal position was recommended, even if the subject of prior harness suspension.” Airway management may determine whether a prone or supine position was used again in accordance with standard UK first aid guidance. The sometimes quoted suggestion of recovery in a semi-recumbent or sitting position was considered to be without any sound evidence base and may prove dangerous through prolonging the lack of blood return to the brain.

Other discussion followed on the management of persons rescued from fall prevention and the possibilities of further research in this area. There was general agreement that the review was welcomed, as clarity was required for first responders and first aiders. Following the meeting some further comments were gratefully received by email and post.

Suspension Trauma Workshop Stakeholders, 30 April 2008

Selly Oak Hospital x 2 representatives

Warrington Hospital

London Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Dorset Ambulance Service

UVSAR

Simian Risk Management

William Hare Limited, Brandlesholme House

Fall Protection Associates

IKAR GB

Central Highrise Ltd

Relative Solutions

Maritime and Coastguard Agency x 2 representatives

USR

BCRO

Chairman MR E &W

IRATA x 2 representatives

Safesite (WAHSA rep)

Spanset (UK) Ltd

Rig Systems Ltd

National Access and Rescue Centre (NARC)

Eastwood & Partners

British Red Cross

CMO, St John Ambulance

Scottish Power

Chairman of IRATA's Equipment Committee

HSE x 3 representatives

HSL x 5 representatives

1 Seddon P. Harness suspension: review and evaluation of existing information CRR 451/2002, HSE Books, HMSO, Norwich; 2002.

Zipes D.P, Libby P, Bonow R.O, Braunwald E. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 7th Ed. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia; 2005.

3 Various, Falls into the rope: skull injuries in alpine regions Papers of the Second International Conference of Mountain Rescue Doctors (Austria) (1972) German to English translation by HSE Language Services Transl. No. 16372(I).

4 Flora G, Margreiter R, Dittrich P, Stuhlinger W. Hanging tests – conclusions for the mountaineer. Papers of the Second International Conference of Mountain Rescue Doctors (Austria) (1972) German to English translation by HSE Language Services Transl. No. 16372(I).

5 Damisch C. Schauer N. Wie sicher sind Anseilgurte? (How safe are harnesses?) (1985) German to English translation by HSE Language Services. Transl. No. 16389 (B) from German magazine Bergsteiger & Bergwanderer, S M G Stiebner- Median Gmbh, Munchen, Germany.

6 Petermeyer M, Unterhalt M, Das Hängetrauma (Suspension trauma) German to English translation by HSE Language Services. Transl. No. 16367(A) Der Notarzt 1997;13, 12-15

7 Harbour R.T. SIGN 50 A guideline developer’s handbook. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Edinburgh; 2008.

8 Turner N. L., Wassell J.T., Whisler R. Zwiener J. Suspension Tolerance in a Full- Body Safety Harness, and a Prototype Harness Accessory, J. Occup.Environ. Hygiene 2008; 5:4, 227 — 231.

9 Madsen P, Svendsen L B, Jorgensen-L G et al. Tolerance to head-up tilt and suspension with elevated legs Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1998; 69:8, 781-784.