Return-on-Investment (ROI) Analysis of Education and Training in the Construction Industry

Summary Statement

This report reviews Return-On-Investment (ROI) to education and training in the construction industry and makes recommendations for the further development of a skilled workforce.

1999

CCIS is multidisciplinary research program studying long-range issues that face the construction industry and is supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Construction Industry Institute (CII), and others. An Advisory Board composed of industry executives provides overall direction for CCIS while a Thrust Area Coordination Committee composed of thrust area leaders meets regularly to provide short term coordination. As a starting point, CCIS has initiated research in four areas of pressing interest for the construction industry: Owner/Contractor Work Structure, Fully Integrated & Automated Project Processes (FIAPP), Construction Workforce Issues, and Technology.

| Bennet, Daniel J.

National Center for Construction Education & Research . President |

McCarron, Doug.

United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America. General President |

| Bush, David M..

Adena Corporation. President and CEO |

Kennedy, Theodore C.

BE&K . Chairman |

| Hedman, Ken.

Bechtel Group, Inc.. Construction Operations |

Mortell, James W.

Cherne Contracting. Senior Vice President |

| Jeffress, James S.

DuPont Engineering. Construction Manager |

Underwood, J. Kent.

Solutia, Inc. Manager, Project Management |

The reader is reminded that the authors, listed below, remain responsible for any deficiencies remaining in this report.

Robert W. Glover, Ph.D..

Donald W. Long.

Carl T. Haas, Ph.D., PE

Christine Alemany.

Specifically, this report provides a comprehensive review of the state of the art in the analysis of the Return-On-Investment (ROI) to education and training and makes recommendations for advancing the construction industry into a prominent leadership position in using training and results-based evaluation to improve the development and utilization of a skilled workforce.

In general there are two separate approaches to this subject, each with its own literature, analytical tools, and standards for judging quality of results --the business practitioner approach and an academic approach, which stems from human capital theory in economics. The business practitioner approach to this subject emphasizes logic, simplicity, transparency, and practicality. By contrast, the academics emphasize scientific rigor and replicatability. Economists have distinguished returns from three different perspectives --from the point of view of the individual being trained, from the perspective of the government, public or taxpayer, and from the point of view of the employer. Surprisingly, the perspective of employer may be the least well developed in academic literature.

Due to several challenges, barriers, and problems which remain to be overcome, both approaches can be properly categorized as "in a developing stage." Thus, while ROI analysis is a well established decision tool in the acquisition of physical capital and equipment purchases, its application remains a cutting-edge development in the arena of human capital. From an academic perspective, three central problems are obtaining accurate measures of the full costs, measuring benefits without relying on subjective estimates, and perhaps most difficult, isolating the impact of the training on changes in performance. To have most confidence in their results, academics evaluators favor comprehensive evaluation designs with components including a process evaluation, an impact analysis, analysis of participant perspectives, and a benefit-cost analysis. This approach generally yields not only a more valid evaluation but better understanding of what is going on "behind the numbers." Even leading advocates of training evaluation in business, such as Donald Kirkpatrick, recommend a multilevel approach to evaluating training, to include (1) a survey of trainee reactions to the training, (2) assessment of learning gains achieved, (3) validation that the learning has been applied or changes behavior in the workplace, and (4) documentation of results or outcomes in terms of company goals. While certainly desirable, such comprehensive approaches can be quite expensive and intrusive on business operations; and thus are relatively rarely implemented in practice. Business practitioners prefer approaches that emphasize practicality, simplicity, transparency, and efficiency.

Given the growing recognition of training as an important factor in economic competitiveness, considerable attention is currently being devoted to the subject of return on investment in training to firms. With all the effort underway, advances in methodology may be forthcoming soon.

ROI analysis offers promise as a tool to improve both the effectiveness and efficiency of education and training in the construction industry, as well as a device to promote expansion of training efforts within the industry. Our research concludes with a recommendation that the construction industry take advantage of both approaches—through academic studies of the returns to training of associations at the industry or "macro" level and by developing a practical "ROI in Training Toolkit" for use by business practitioners at the "micro" or company level. Within the construction industry, work sponsored by the National Center for Construction Education and Research, the Construction Industry Institute, CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training, and the Center for Construction Industry Studies could all be helpful resources contributing to this effort. In addition, construction industry leaders should monitor the progress in developing and using ROI tools in other industries, especially through such organizations as American Society for Training and Development and others, as well as advances in the academic literature on this subject.

Chapter 1: Introduction and Background

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Background

1.3 The Challenges and Benefits of Measuring ROI

1.3.1 The challenge of conducting cost-effective ROI evaluation of training

1.3.2 The benefits of conducting cost-effective ROI evaluation of training

1.3.3 Preconditions to training impact

1.3.4 Training Evaluation: Business Research

Chapter 2: Training as Strategic Variable

2.1 Rationale for Investment in Training

2.1.1 Linkage between Quality and Training2.2 Profile of Training Firms and Recipients

2.1.2 Advantages of Employer-Provided Training

2.1.3 Rationale for Investment in Training in the Construction Industry

2.1.4 Unique Industry Characteristics

2.1.5 Industry Structure

2.1.6 Workforce Needs

2.1.7 Goals of Training in Construction Industry

2.2.1 Job Characteristics

2.2.2 Firm Characteristics

2.2.3 Worker Characteristics

2.2.4 Summary

2.3 Extent of Training Investment in All Industries: Employer-Sponsored Training

2.4 The Extent of Training in the Construction Industry

2.4.1 Apprenticeship

2.4.2 Training by Associations and Consortia of Firms

2.4.3 Informal Training

2.5 Direction of Training Investment

2.6 Barriers to Employer-Provision of Training

2.6.1 Barriers to Training in Construction Industry

2.6.2 Summary

Chapter 3: Relationship between ROI Evaluation and Training

3.1 Human Capital Theory

3.2 Industry Best Practices: The ASTD Benchmarking Forum

3.2.1 Contributing to a System of Continuous Improvement of Training

3.2.2 Efficient and Effective Management

3.2.3 Summary

3.3 Research on Returns to Training

3.3.1 Academic literature

3.3.2 Business literature

3.3.3 Research on Returns to Informal Training

3.3.4 Returns to Training in Construction Industry

3.4 Academic Approaches to Training Evaluation

3.4.1 Academic Evaluation Techniques

3.4.2 Academic Studies of Construction Industry

3.4.3 An Integrated Evaluation Model

3.4.4 Need for a Comprehensive, Systemic Perspective

3.5 Business Approaches to Training Evaluation

3.5.1 Kirkpatrick's Classic Training Evaluation Model

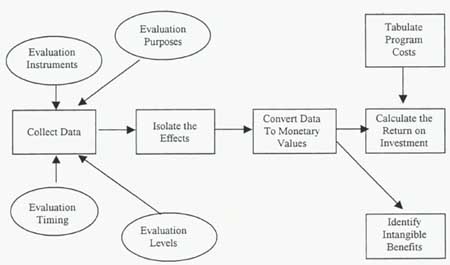

3.5.2 Phillips' ROI Model

3.6.1 Guiding Principles for Implementing ROI

3.6.2 Findings and Future Work

Table 2.1 Selected Training Expenditures per Employee by Industry in 1994 (Dollars)

Table 2.2 The Number of Individuals Entering Apprenticeships, by Initial Year of Registration and Most Common Industry Sector, 1991-1995

Table 3.1. Complementary Components of a Comprehensive Evaluation

Table 3.2. Bundles of Variables for Econometric Model of Training and Firm Performance

Table 3.3. Paradigm Shift in Training Evaluation

Table 3.4. Status of Training Evaluation by Kirkpatrick's Four Levels

Table 3.5. A Systemic Evaluation Model: 18 Steps

Calculating Return-on-Investment (ROI) is a practice of modern management used in the analysis of many business strategies and operations. Perhaps the most popular application of this tool is in the analysis of purchase decisions for investments in capital equipment or technology. ROI is simply a measure of benefit versus cost. Expressed as a percentage, ROI is determined by total net present benefits divided by total net present costs. Benefits and costs are converted into present values since they usually accrue over extended periods of time.

The specific aim of our research is to develop an understanding of the cost-effective application of ROI analysis to training programs in the construction industry as a means for their continuous improvement. Given the costs and difficulties that have been identified with applying ROI to training at the individual firm level, our research investigates the feasibility and benefits of conducting rigorous ROI analysis by an industry association or consortium of firms, which could pool resources and spread costs across multiple firms. In addition to building a solid empirical research base on training evaluation, this research may conceivably lead to the development and production of an "ROI in Training Toolkit," comprising a set of cost-effective, empirically-tested ROI instruments and related support materials, which construction industry owners and contractors could use to plan and implement ROI analysis designed to maximize the returns from training investment.

This report presents the findings of the initial phase of this research and suggests future work. It investigates the relationship between training and evaluation to identify the potential benefits and costs of ROI analysis of employer-sponsored training in the construction industry. While a long-established business practice, ROI analysis remains on the frontier in measuring the impact of training.

Planning and evaluation can enhance the contribution training makes to firm performance. To maximize returns from their investments, organizations must plan, implement, and evaluate training effectively. In today's economy, every element of business environment is in motion—technology, work organization, suppliers, customers, employees, corporate structure, industry structure, government regulation. In the words of one management analyst, to compete in this environment, companies need to be "focused, fast, friendly, and flexible" (Kanter 1989).

Our research aims to contribute to the construction industry's planning and operational capacity to meet existing and future workforce needs by attracting, training, and maintaining skilled workers. This report provides a comprehensive background on ROI and makes recommendations

for advancing the construction industry into a prominent leadership position in using training and results-based evaluation to improve the development and utilization of a skilled workforce.

1.2 Background

The present economic landscape is dominated by three major forces: 1) an internationalized or global economy in which it is more difficult to set prices, outputs, wages, and working conditions according to domestic standards; 2) rapid technological change, especially the "third industrial revolution" generated by microelectronics and information technologies; and 3) rising customer expectations of quality and intensifying volatility in consumer demand patterns (Marshall 1994). In response to these forces, the needs for workforce flexibility and skill requirements are rising and overall investments in training are increasing (U.S. Department of Labor 1996; and National Center on Educational Quality of the Workforce 1994). However, most experts agree much more training is needed and that it must spread beyond the managerial and professional ranks where it is now concentrated. Ideally, training could gain greater support within the industry and become effective and responsive to industry needs if practical tools were available for more rigorously evaluating the performance and effects of training. In brief, this is the promise and appeal of ROI.

Over the last two decades, in response to the intensifying competitive pressures of the new economic landscape, training has gained increased prominence as a major strategic variable in firms and industries (Carnevale 1991; Marshall 1994; and Bassi 1997). The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), the largest industrial trade association in the US, recently adopted a resolution to make worker training one of its top priorities. With this increased prominence has come the recognition of the need for applying rigorous planning and evaluation to training. The focus on ROI as a critical element in the development, maintenance and improvement of training systems follows national trends in other industries (Robinson 1989; Kirkpatrick 1994; Phillips 1994; Phillips 1996; Phillips 1997; and Bassi 1997).

In the construction industry, intensifying competitive pressures have been particularly acute, simultaneously demanding greater project complexity and shorter time restrictions (CII 1992). Increasingly over the last decade, the attention of the construction industry has focused on training as a strategic factor in its long-term vitality and growth (Liska 1994; Business Roundtable 1997; and Krizan 1997). These increasing demands for a highly skilled workforce have arisen at a time when the construction industry faces serious problems in retaining existing workers and recruiting new workers. The decline of young people entering the industry, combined with the average age of 47 for craftsmen, places the industry in serious need of attracting talent. According to the National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCER), the construction industry is short approximately 240,000 workers per year, with that number continuing to increase. High rates of employee turnover also exacerbate the problems. The industry tends to lose many of its personnel well in advance of retirement age, which greatly diminishes the returns from training investments.

A variety of studies has concluded that training efforts are inadequate to meet the present or future needs of the construction industry (Dorsey 1990). A strong consensus has emerged that the construction industry must take action now on building a world-class training system. At the forefront of this attention is the recognition that results-based evaluation or ROI is an essential tool for aligning training with firm and industry performance objectives. ROI extends the strategic and operational rigor of quality management practices to training systems. Hence, in 1997, the Construction Committee of the Business Roundtable published a specific challenge to owners, contractors, and contractor associations, and labor organizations, that they "must work jointly to develop methods to evaluate training delivery and its impact" (Business Roundtable 1997, p. 10-11).

Research into this subject is needed because of the serious shortcomings of economic research into training and its impact on firm performance. In neither the academic and business literature has a research consensus been reached over appropriate procedures to measure the financial returns on training investment nor to determine the direct relationship between training inputs and bottom-line profit and cash flow outputs. Only a small percentage of US firms currently measure the return to their investments in training; thus most firms know little about the direct relationship between training and firm performance (Kirkpatrick 1996; Phillips 1997; and Alder 1994). Consequently, measurement of ROI is currently a major focus in research on the field of human resource (HR) management.

Much of the academic and business focus over the last two decades has focused on other industries other than construction, especially manufacturing. (For example, see MacDuffie 1995; and Kling 1995). In 1996, the construction industry provided over 5 million jobs and 1.5 million support jobs. Yet despite its clear importance to the national economy, few empirically tested studies exist (Finkel 1997).

Further, labor market research in workforce development has largely overlooked training of front-line incumbent workers. Instead, existing research has focused on employer-sponsored training for managers and professionals, or on public training programs for the unemployed and disadvantaged groups. This failing reflects a more serious neglect of front-line workers in both private and public expenditures on training (Ferman 1990; Carnevale 1991; and Lillard and Tan 1986).

1.3 The Challenges and Benefits of Measuring ROI

1.3.1 The challenge of conducting cost-effective ROI evaluation of training

The task of conducting rigorous and reliable ROI evaluation of training exceeds the resources and expertise of most individual construction owners and contractors. A significant aspect of the proposed research is to present a plan for this task to be accomplished at the association or consortium level. Cost-effective ROI evaluation of training must overcome the following challenges and obstacles:

- Attribution of effects to training is very difficult due to the influence on firm performance of a complex myriad of other factors. Variables such as markets, revenues, costs, interest rates and many other factors, enter into profit determination, making it difficult to isolate the impact of any incremental training expenditure. Most ROI figures aren't precise, though they tend to be as accurate as many other estimates that organizations routinely make.

- Evaluation is complicated by serious problems with data collection and measurement.

- Costs of training are generally known up front, often before the training takes place, but benefits may accrue slowly over time and may depend on such unpredictable factors as turnover rates among workers who are trained.

- Objectives of training are often murky and the rate of return cannot be measured if the meaning of return cannot be defined in quantifiable terms.

- Cultural resistance may be the main reason ROI is not measured for training. Some managers view ROI studies simply as promotion and marketing by the training department. Moreover, the "best practice" companies in terms of training are often the most resistant, accepting the value of training as an article of faith.

- High costs of evaluation can be a major barrier, especially if they exceed the benefits from training.

- Informal training and learning-by-doing, which are important sources of learning, are embedded in production and therefore very difficult to measure.

- The inability to attribute causation to the training from before and after comparisons due to the lack of a valid control group.

1.3.2 The benefits of conducting cost-effective ROI evaluation of training

Although the challenges are formidable, they are not insurmountable. Business people aren't looking for unassailable scientific proof. They only want sufficient evidence to develop a plausible and reasonable business case. Moreover, the effective deployment of ROI analysis to investments in training offers the following benefits:

- It will enhance understanding of human capital as both a significant factor of productivity growth and a critical variable in the process of technological change.

- ROI analysis can be a means to bring "continuous improvement" of training through greater emphasis on documentation, measurement and feedback loops, which is consistent with Total Quality Management and ISO-9000 management practices.

- ROI can provide critical information for addressing the serious problem of poor transfer of knowledge and skills from the classroom to the workplace.

- ROI analysis can bring greater accountability and improved efficiency to the training function of firms.

Three conditions must exist before human resource practices can improve economic performance:

- Employees must have the skills and knowledge that managers lack;

- They must be given the motivation to apply them; and

- The production system must channel their efforts towards performance improvements (Levine and Tyson in Blinder 1990; and MacDuffie 1994).

Researchers have found that the returns to training are dependent upon several other important production factors and that training is best understood in the larger context of a firm's entire set of managerial and production strategies, functions and practices. Business returns to training are optimized when this entire set forms a coherent "organizational logic" supportive of training. Thus, a comprehensive ROI evaluation of training should take into account such factors as managerial leadership, company/project culture, work practices (e.g., teaming and multiskilling), and incentive systems (e.g., compensation and recognition for performance).

1.3.4 Training Evaluation: Business Research

Many managers believe ROI is too costly or takes too much time. Such skepticism arises because few firms conduct ROI evaluation of training, and many of the existing studies lack scientific rigor. The business ROI approach addresses management's concerns of ROI effectiveness.

In comparison to academic methods, the business ROI approach is transparent, practical, and relatively easy to implement, and can provide immediate feedback. The business ROI approach is based on benefit-cost analyses, which makes variables and their relationships to outcomes clear and explicit. However, it relies heavily on estimation by managers, which lessens empirical rigor (e.g., estimation of the percentage of influence from other factors).

Can the return on investment in skills training be accurately assessed in the construction industry? Can this be accomplished in a cost-effective manner? These are the essential questions of interest to industry. They require investigating the current status of training, its strategic role, and its relationship to firm performance; the current state of evaluation--in both the academic and the business literature and the capacity of individual firms and the industry as a whole to conduct cost-effective, rigorous ROI.

It is unlikely that the construction industry will meet this challenge on its own. The fragmentation of the construction industry makes it very difficult to meet this challenge in a comprehensive and systematic way. Construction is a $400 billion industry that supports almost 1 million general contractors, 50,000 architect and consulting engineering firms, 25,000 building materials dealers, over 70 national contractor associations, 15 major building and construction unions, 10,000 building-code jurisdictions, and over 8 million employees. Moreover, relations between the union sector and the nonunion sector of the industry are often contentious and adversarial. Such fragmentation of the construction industry, in combination with the trend of increasing project complexity and shorter time restrictions, greatly limits its ability to build effective training evaluation systems.

The considerations outlined above make the leadership of the Construction Industry Institute and the Workforce Thrust Team of the Center for Construction Industry Studies both timely and greatly needed. Further efforts in this arena could contribute significantly to addressing the needs of attracting and retaining a skilled construction workforce.

This report contains five sections. The second section examines training, its returns, and the current extent and direction of training investment. The third section surveys the present state of training evaluation, looking at both academic and business approaches. The fourth section focuses on ROI. The report concludes with findings and suggests an path forward in this research arena which would include identifying ROI benchmarks and performance metrics specific to the construction industry, developing a cost-effective "ROI in Training Toolkit," and keeping abreast of developments in other industries in this arena that is receiving so much current attention.

2.1 Rationale for Investment in TrainingAs a response to competitive pressures, training serves important individual, business, and social goals, including the following:

- upgrade skills continuously;

- improve performance;

- enable individuals adapt to changes in strategy, structure, technology or market conditions;

- help people reenter the labor market;

- attract best skill matches to industry or organization;

- provide potential for promotion and flexibility;

- improve organizational competitiveness; and

- develop their human capital.

In the most recent national survey of employer-provided training conducted in 1993, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics found the most common reason establishments provided training was to provide the necessary skills specific to their organization (75 percent). Other reasons for providing formal job skills training were to keep up with changes in technology or production methods and to retain valuable employees (BLS 1995). Training also contributes to improved job satisfaction, which researchers have found to be strongly correlated to career advancement (Finkel 1997).

2.1.1 Linkage between Quality and Training

The international ISO 9000 standards, which are set by the Geneva-based International Organization for Standardization and increasingly necessary for full participation in global commerce, dictate specific requirements for corporate training. Section 4.18 states the requirement of training for every employee whose work "affects quality." To assure compliance, firms have developed comprehensive training systems based on rigorous documentation of training needs and practices. Many large firms are demanding that their primary suppliers obtain ISO 9000 registration as well. In addition, ISO-9000 adds two further stipulations: Training must be viewed as a strategic corporate issue, and its effectiveness must be evaluated periodically, preferably at least once per year. This tight linkage between quality and training also is reinforced by criteria established in the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award, which highlight the importance of human resources. The Australian counterpart to the Baldrige Award places even stronger emphasis on human resources.

2.1.2 Advantages of Employer-Provided Training

Over the past two decades, education experts and labor economists have studied the effectiveness of various forms of education and training programs. One of the strongest findings is that participation in education and training generally is closely linked to subsequent gains in employment and earnings (Eck 1993; Bishop 1994). John Bishop, a labor economist, found in a recent study that employer-provided training is generally more effective than school-based training. He attributed this finding to the following unique features of employer-provided training:

- What is learned is much more likely to be used within a short time period

- Trainees are more motivated not only because skills are more likely to be used, but also because promotions and pay increases generally go to those who do well;

- Training is often tutorial in nature;

- Training is provided by supervisors and coworkers who are aware of trainee's progress and can give helpful feedback;

- Equipment and materials to complement training are generally available and up-to-date;

- Trainers are generally held accountable for trainee's success;

- Employers providing training have strong incentives to select most cost-effective strategies and to assure trainee's time is used most efficiently.

2.1.3 Rationale for Investment in Training in the Construction Industry

The need for more effective and comprehensive training has long been a concern in the construction industry. In the early 1980s, the Construction Industry Cost Effectiveness program of the Business Roundtable produced a series of research reports which recognized the importance of training for the long-term vitality of the industry (Business Roundtable 1983). More recently, the Business Roundtable and a growing number of industry experts have amplified the seriousness of this need and specifically recommended the development of ROI evaluation as a crucial driver of the continuous improvement of training (Business Roundtable 1997; Liska 1994; Krizan 1997; Korman and Reinain 1997; and Korman 1997).

2.1.4 Unique Industry Characteristics

Construction is a labor-intensive industry with a strong reliance on specialized skills and training. There is a lower capital-for-labor substitution in construction than other industries (Finkel 1997). Major trends include an increase in project complexity and time restrictions. As technology progresses and competitive pressures continue to increase in other industries, the construction industry faces increasing customer demands. At the same time, the construction industry is large, fragmented, communication-sensitive, archaic, and complex. Construction labor markets have several unique characteristics. The mix of firms and employees working on a project constantly changes from start to finish. Jobs are of short-duration. Technological and financial forces and the vicissitudes of the weather exacerbate employment instability (because much of the work is performed outdoors). The high levels of debt required to finance projects make the industry especially sensitive to changes in interest rates and credit availability. Many construction skills are marketable outside industry. Employees are often more attached to their crafts than they are to individual employers. Firms therefore lack incentives to invest in training since their investments frequently walk away.

Some apprenticeship sponsors in the industry have attempted to protect themselves from losing their investments by instituting "scholarship-loan" agreements whereby apprentices commit to work for the sponsoring employer(s) for a specific number of years. If they leave employment early and work elsewhere in the industry, they are obligated to pay back a portion of the cost of the training, based on how long they stayed. These "scholarship-loan" agreements are written contracts signed by the apprentice and his/her sponsor. The concept was originated by the United States Navy to finance the college education expenses of their recruits shortly after World War II. Although anecdotal evidence and apprenticeship sponsor testimony is available supporting the effectiveness of this device to protect investments in training, no careful empirical evidence has yet been accumulated to document its efficacy.

The industry is characterized by a high degree of fragmentation. Construction is a $400 billion industry that supports nearly 1 million general contractors, 50,000 architect and consulting engineering firms, 25,000 building materials dealers, over 70 national contractor associations, 15 major building and construction unions, 10,000 building-code jurisdictions, and over 8 million employees. The highly competitive nature of the industry, combined with such a division of leadership and direction, hampers its productivity and limits its responsiveness to changing markets. In 1993 there were 598,255 construction shops; of these, almost 83 percent had fewer than ten employees (US Department of Commerce 1993). There is a lack of vertical integration; only relatively few companies, such as Bechtel and Fluor Daniels, have developed into large, vertically organized entities able to reap significant economies of scale.

In 1990, Robert Dorsey published his findings on current and near-future needs for education and training in the construction industry, covering the full range of construction positions from subjourneyman to senior executives. He concluded that existing education and training efforts were not adequate to meet either present or future needs of the construction industry. Education and training are a continuum, with lower level positions requiring special training and on-the-job experience, while upper level positions require approximately equal portions of formal education, special training, and on-the-job experience. Closely coordinating continuing education with on-the-job experience greatly increases its effectiveness (Dorsey 1990).

Other research has identified the following workforce issues as critical to the success of the industry:

- Need for craft training

- Need for supervisory training

- Attitude of today's workforce

- Work ethics

- Motivation

- Complexity of projects

- Adversarial relationships

- Burnout

2.1.7 Goals of Training in Construction Industry

Demographic changes and competitive forces have made improving and expanding training a vital concern for recruitment, retention and maintenance of a skilled workforce.

Recruitment. The number of young people entering the industry have declined. This has caused the average age of construction craftsmen to rise to 47 years old. The National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCER), citing statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, notes that the construction industry is short approximately 240,000 workers per year, with that number continuing to increase. The industry suffers from high turnover and a poor public image.

Retention. Equal attention should be paid to retention as well as recruitment to offset the "30-year-old" exiting syndrome (whereby personnel tend to leave the industry after reaching the age of 30). Shift of experienced workers to other industries in their prime working years represents a costly loss of human capital. Too many craftworkers leave the industry early in their careers; so that the average age of journeymen who remain in construction has risen to mid-40s range and continues to increase. In addition, literacy level of the workforce is at 40-year low at the same time that new technologies and competitive pressures are requiring higher skills, especially in mathematics.

Equity. Training is an important gateway into the construction industry for minorities and women. Construction industry response to civil rights pressures has led to many advances in minority employment, though often not without conflict or adversarial proceedings. Given the increasing levels of minority and female representation in the US workforce, outreach and training initiatives for minority groups and women in construction will carry even greater importance in the future. Problems of under-representation of minorities and especially women persist in construction; occupational segregation and discrimination restricts their entry into the best jobs, thereby diminishing current and future earning power. Continuation of inefficient and incomplete utilization of the full potential workforce imposes significant costs both to the construction industry and to society.

2.2 Profile of Training Firms and Recipients

Bishop (1994) summarized the differences among workers who receive formal training and those who do not. Holding other worker characteristics constant, the likelihood and amount of formal training in a given year varies for workers according to the characteristics of the jobs they hold, the firms for whom they work, as well as the characteristics of the worker themselves.

Workers are more likely to receive training if their jobs have the following characteristics:

- High value added jobs where the individual has great responsibility

- Cognitively complex jobs (e.g. professional, technical and managerial jobs)

- Sales jobs for complicated, changing and customized products

- Use expensive machinery on their job

- Regular, non-temporary jobs

- Full time jobs

- Jobs where the skills learned are not useful at many other firms in the community, which suggests that training intensity rises when firms have monopolistic power in the local labor market.

Workers are more likely to receive training if they work in firms with the following characteristics:

- Larger establishments

- Large unionized manufacturing establishments

- Firms which have multiple establishments

- Companies employing flexible or high performance production systems

- Industries or firms experiencing rapid technological progress and rapid output growth.

- Firms which have not experiences a competitive crisis in the last decade

- Industries which have established industry standardized and certified training

- Firms which have long probationary periods for new hires

- Firms where firing an employee is reported to be difficult once the probationary period is over

- Industries with low unemployment rates. Training appears to increase when demand for an industry's product is high and capacity utilization is high.

- Firms located in areas of low unemployment.

- Employment is located in metropolitan areas

- Employment is located outside the south

Workers are more likely to receive training if they have the following characteristics:

- Many years of education, in particular workers who have completed high school or college

- Scored well on tests assessing verbal, mathematical and technical competence when they were in school and who have been out of school for many years

- With vocational training that is relevant to their current job

- Recently hired

- Expected to have low rates of turnover

- Male

- Married

- White

Most employer-provided formal training is acquired by college graduates. Those receiving training are more likely to be managers, professional or technical workers, as well as workers in all occupations who are employed by large firms. Additional years of schooling raise the probability of participating in off-the-job training or an apprenticeship. Unionized workers are more likely to receive training, while non-unionized workers are more likely to have participated in off-the-job training that they paid for themselves. Two of the most important characteristics in the probability of receiving training are race and gender. Women and non-whites are less likely to receive company-provided training or to be in apprenticeships. When women do receive company-provided training, the duration of the programs tends to be much shorter than for men (Barron, Black, and Loewenstein 1989; and Altonji and Spletzer 1992).

2.3 Extent of Training Investment in All Industries: Employer-Sponsored Training

Precise information on the total expenditures for employer-sponsored training in the US is not available. The determination of the extent of training in the entire economy depends on definitional and measurement issues, and so one can expect estimates to differ and comparison across surveys to be highly problematic. Nonetheless, an examination of the best, most recent studies reveals a range of $55 to $60 billion in 1995. According to Training magazine's 1996 Industry Report, US companies budgeted nearly $60 billion on training in 1995, which was close to the total amount spent on post-secondary education, and provided nearly two billion hours of instruction. A manufacturing firm with more than 100 employees budgeted an average of $500,000 for training.

Confirming these findings, the American Society for Training and Development (ASTD) estimated that employers spent $55.3 billion on training in 1995. These expenditures included direct and indirect expenses. Direct expenses included salaries and benefits for training personnel and contractors; purchase and maintenance of equipment; cost of space for training; outside trainers or outside training companies; tuition reimbursement; and travel and living expenses of employees while attending off-site training. Indirect expenses included wages, salaries and fringe benefits of employees while they are in training.

The amount of training varies significantly by employer size, with large employers providing the lion's share. According to a 1989 ASTD study, 90 percent of all job-related training occurs in only 15,000 companies, which is less than one percent of American employers. Only a small number -- perhaps 100 to 200 companies—invest more than 2 percent of payroll in formal training.

The most authoritative training estimates are produced by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Its most recent survey of employer-provided training found that virtually all large establishments provided formal training to their employees in 1993, compared with only 69 percent of establishments with fewer than 50 employees. Overall, 71 percent of employers provided some type of formal training to their employees (US Bureau of Labor Statistics 1996). Formal training, as defined in the BLS survey, is training that has a structured format and a defined curriculum, and may be conducted by supervisors, company training centers, businesses, schools, associations, or others. It may include classroom work, seminars, lectures, workshops, and audiovisual presentations. The survey measured six different types of training provided or financed by employers: orientation, safety and health, apprenticeship, basic skills, workplace-related, and job skills.

Other major findings of the BLS survey included the following:

- The provision of formal training varied somewhat across industries. Slightly fewer than 60 percent of all construction establishments provided formal training of any kind in 1993. This compared with roughly 3 out of every 4 establishments in the finance, insurance and real estate industry; the services industry; and the transportation, communications and public utilities industry.

- Some types of formal training were more prevalent than others. Nearly half of all establishments provided formal job skills training in 1993, while orientation, safety and health, and workplace-related training (training in areas such as communication skills, diversity, and workplace laws) were provided by about a third of establishments. Fewer than 3 percent of all establishments provided formal training in basic reading, writing, arithmetic, and English language skills during 1993. Larger establishments were more likely than smaller ones to provide formal training of all types.

- Nearly two-thirds of establishments that did not provide formal job skills training in 1993 reported that "on-the-job" training satisfied their training needs. Fewer than 10 percent reported that the cost of formal training was too high or that they were unwilling to provide formal training due to a fear of losing trained employees to other employers.

Table 2.1 Selected Training Expenditures per Employee by Industry in 1994 (Dollars)

| Characteristic | Total 50 or more employees | Mining | Construction | Manufacturing Durable | Manufacturing Non-Durable | Transportation Communications and Public Utilities | Wholesale Trade | Retail Trade | Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate | Services |

| Tuition reimbursements |

51 |

50

|

16

|

74

|

64

|

62

|

56

|

22

|

74

|

45

|

|

Wages and salaries of in-house trainers |

139

|

299

|

64

|

98

|

188

|

334

|

108

|

31

|

202

|

14 6 |

| Payments to outside trainers |

98

|

160

|

60

|

95

|

157

|

135

|

108

|

21

|

213

|

87

|

| Contributions to outside training funds |

12

|

12

|

102

|

22

|

1

|

7

|

18

|

5

|

0

|

7

|

| Subsidies for training received from outside sources |

5

|

0

|

1

|

9

|

7

|

3

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

8

|

2.4 The Extent of Training in the Construction Industry

A wide spectrum of training in the construction industry is available, ranging from formal programs including structured apprenticeships, journeyman upgrade training; modular, task-oriented training and pre-apprenticeships for disadvantaged and minority individuals (generally

financed by government to prepare individuals to enter apprenticeships) to informal, casual observation of coworkers. This spectrum traditionally has reflected the respective training capacities and investments of the union and open-shop sectors, with the former significantly

exceeding the latter. However, while training in the industry is currently in a state of flux, one trend has been toward expansion of training by the open-shop sector. This shows promise of a healthy competition between the two sectors. Yet important gaps remain. A 1997 Kentucky

study of registered apprenticeships found the union sector had more apprentices, higher completion rates, and produced more skilled journeymen who were more diverse in race and gender. Union apprenticeships also comprised a broader scope of trades; whereas nonunion apprenticeships

were heavily concentrated in electrical trade (Londrigan and Wise 1997).

The open-shop sector claims to account for almost 80 percent of the dollar output produced by building and construction firms nationally (Finkel 1997, p. 6). Yet the bulk of formal structured training for craftworkers is still performed by the union sector of the construction

industry. There clearly remain problems of mindset in the open-shop employers who do not yet adequately value training (Business Roundtable 1997).

In America, the construction industry historically has made greater use of apprenticeship than any other industry. (See Table 2.1.) Construction trades have been consistently represented among the top apprenticeship occupations. (See Table 2.2). Jointly administered apprenticeship programs in the union sector reflect the strong training commitments of both unions and employers and optimize investments in training by spreading costs among all stakeholders and sharing the benefits of trained employees across firms. Many workers have stronger attachments to the union sector due to their health and welfare benefits. Since these apprenticeships produce workers with the same skills who remain in the union sector, employers are often able to replace one worker with another similarly trained worker. Apprentice training provides deep skill development along traditional craft lines.

Apprenticeship combines OJT and classroom training that leads to journeyman status and a nationally recognized credential. Formally structured and well established through a long tradition, it provides in-depth and comprehensive training in a specific trade.

As true in other industries, training is provided by the well-known, larger leading contractors. Smaller, lesser-known firms tend to offer their workers little or no training. Training is primarily focused on management, supervisory or journeymen levels. Neglect of training subjourneymen personnel is a special problem in the open-shop sector.

|

Industry

|

1991

|

1992

|

1993

|

1994

|

1995

|

|

Construction

|

25,376

|

23,937

|

26,832

|

33,620

|

5,976

|

|

Manufacturing

|

7,020

|

5,943

|

6,671

|

6,366

|

7,189

|

|

All Industries

|

53,544

|

52,783

|

56,629

|

62,922

|

55,818

|

SOURCE: Apprenticeship Information Management System (AIMS). AIMS data represent approximately 70 percent of all registered apprentices.

2.4.2 Training by Associations and Consortia of Firms

The construction industry has come to recognize that industry associations and consortial arrangements among firms play a critical role through planning, coordination, and resource pooling in the development and diffusion of high quality training programs (Finkel 1997). In the open-shop sector, the Associated Builders and Contractors (ABC) have developed multi-employer training programs that aim to secure the benefits of pooled resources and certifications. The National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCER), whose sponsors include ABC as well as the Associated General Contractors (AGC)--an organization which has both union and nonunion member firms--develops, produces, and distributes apprentice and craft training programs through a network of accredited sponsors, consisting primarily of trade associations and contractors themselves. The NCCER has an accreditation program and maintains a national registry of trainees. The Center also promotes use of a standardized national curriculum, entitled "The Wheels of Learning," which is modular and task-oriented, the kind of approach to training that is claimed to meet the needs for flexibility and responsiveness in the open-shop sector.

The 1996 BLS survey concluded that 70 percent of all training for the economy as a whole is informal. Throughout the history of the construction industry, the predominant source of training has been informal OJT. In a study of construction apprenticeship, Marshall, Franklin and Glover (1975) found the two most important alternative sources of training were working as laborers or helpers at union sites or informal OJT in the open shop. OJT and formal training are generally found to be complementary, and OJT therefore raises the benefits produced from formal training (Loewenstein 1994). This is especially true in the construction industry, in which formal training of skilled journeymen leads to substantive spillover effects through informal learning.

Informal training, which is embedded in production, is very difficult to measure and to cost out. This factor adds significantly to the challenge of conducting rigorous ROI. Research has documented large measurement errors in OJT variables, along with significant discrepancies between worker and employer estimates of its incidence and intensity (Barron, Black, and Loewenstein 1989). Though informal training costs are difficult to measure, certainly more is spent on informal training than on formal training in the US because informal learning is far more common. Jacob Mincer, the pioneer of labor economists in the study of OJT, estimated expenditures on OJT amounted to $240 billion in 1987, based on amount of time people reported to learning on the job, equal to 11 percent of total compensation, significantly more than the average of just under 1 percent of payroll (or a smaller percentage of total compensation) that US firms spend on training.

2.5 Direction of Training Investment

Conflicting interpretations of workplace change lead to contrasting assessments of the direction of investment in training by firms. On the one hand, the increasing recognition of training as a strategic variable led to the conclusion that it is increasing, especially among "best practice" firms. This is also supported by national surveys of employer training (US Department of Labor 1996; and National Center on the Educational Quality of the Workforce (EQW) 1994). Fifty-seven percent of the respondents in the EQW survey reported having increased the amount of training they provide over the last three years. In addition, several "best-practice" firms were spreading their investments beyond managerial and professional occupations to include front-line workers.

On the other hand, evidence of the disintegration of internal labor markets and more contingent relations between firms and employees suggest declining commitments by firms to provide their own training. Firms increasingly appear to be opting instead to buy or "poach" trained workers from other firms (Cappelli 1997). Management structures have become flatter, and career ladders have become truncated, while the incidence of internal labor markets, with their favorable characteristics promotional and advancement opportunities, earnings gains, buffering from external market forces, long-term stability and security—has diminished considerably. Contingent workers may now comprise as much as one-quarter of the civilian labor force (Bassi 1997). These changes tend to raise the costs and lower the benefits to the firms that invest in training.

Nevertheless, upgrading the skills of current employees is almost always more cost-effective than firing personnel with outmoded skills and replacing them with new employees. Twelve studies based on data from GTE and Western Electric compared the costs of upgrading production workers with different levels of skills with the costs of hiring and training new workers, waiting for the workers to get up to speed, and laying off the original workers. In 11 of the 12 studies, the costs of training existing workers were lower. In the twelfth study, the marginal advantage of hiring from the outside was offset by lower company morale (Ward 1986).

2.6 Barriers to Employer-Provision of Training

International comparisons of training investments has led to the consensus among labor market analysts that American firms under-invest in training and should greatly increase the amount they spend on training. A 1990 study comparing American-owned companies with Japanese and European operations in the US concluded that the foreign-owned facilities spent three to five times as much on worker training. According to Jack Phillips, a training and ROI expert, the US invests only 1 percent of payroll on training, while European firms commit 2.5 to 3 percent and Asian firms spend 4 to 8 percent of payrolls on training (Chase 1997).

In explaining why there is more training in Germany and Japan than in the US, Bishop (1994) lists four primary causes: (1) higher employee turnover in the US; (2) higher cost of capital due to large budget deficit and low savings rate; (3) higher trainability of workers in Germany and Japan; and (4) historically looser American labor markets in which there has been a greater availability of skilled and semiskilled workers on the outside labor market.

Finally, imperfect information about labor supply (applicant skills) and labor demand (jobs and their skill requirements), which greatly hinders the efficient operation of labor markets, is more prevalent in the US Imperfect information reduces the efficiency and effectiveness of job matching, which in turn increases turnover, lowers wages, and lowers productivity, all of which lower the incentive to invest in general training.

In addition to labor market dynamics, tax policy, managerial culture, accounting systems, and short time horizons in US capital markets also contribute to less spending on human capital than on physical and equipment capital. Generous depreciation schedules available to offset purchases of capital equipment have long made investment in physical capital more attractive to industry than investment in human capital. The dominant rewards, pressures and signals that have largely influenced management behavior over this century continue to direct managers to regard human resources as expenses to be minimized instead of assets to be developed and optimized. Conventional accounting systems, which have essentially remained unchanged over the past 50 years, are not designed to provide data or feedback for decision making and planning about the use of human resources; and their focus on the short-term fails to capture the long-term value creations of training (Carnevale and Schultz 1990).

2.6.1 Barriers to Training in Construction Industry

In addition to the general barriers that affect all industries, there are barriers that specifically affect the construction industry. Liska (1993) investigated the reasons that were given by construction contractors for not training their employees. In order of decreasing significance, these were as follows:

- Lack of money

- Lack of time

- Lack of knowledge

- High employee turnover

- Workforce too small

- Past efforts not effective

- Hire only trained workers

- Lack of employee interest

Other significant barriers included the lack of: quality standardized training curriculum; support materials; resources and expertise; professional development; and technical assistance.

Training investment is increasing, yet few firms approach it systematically. Commitment to training is an essential precondition for developing a cost-effective system of ROI. This entails both commitment from top management as well as awareness and understanding of the importance of training throughout the organization. Training also needs to be incorporated into business strategic planning. Strategic planning itself is not practiced at many firms, especially smaller ones, which make up the majority of the construction industry. Planning does offer many challenges; it can be time-consuming, costly, and beyond capacity of existing available resources. Needed information many not be conveniently available, too many variables may need to be considered, or the future may pose too many uncertainties.

Training departments need to have the capacity and expertise to contribute at a strategic level. Prior to developing ROI systems, companies must meet the enormous challenge of transforming their culture into a "learning organization" (Senge 1990; and Marshall 1994). And yet the issue of the proper sequencing of training and ROI reforms arrives is a paradox. While ROI must await this change to be fully effective, it can also serve as a powerful driver to bringing about this transformation in culture.

Conceptually, the application of ROI analysis to training is a logical extension of human capital theory in labor economics, pioneered by Theodore Schultz and Gary Becker, which posits that upward-sloping wage profiles reflect investments in human capital. Human capital theory holds that education and training inputs (human capital) are directly related to worker productivity and thereby wages (factors contributing to return on investment). Jacob Mincer extended the model to include on-the-job Training (OJT). Understanding the returns to investment in human capital can provide insight into the comparative quality and effectiveness of different training programs.

Researchers have found that training is best evaluated in the larger context of a firm's entire set of managerial and production strategies, functions and practices. Business returns to training are optimized when this entire set forms a coherent "organizational logic" supportive of training. Furthermore, three conditions must exist before human resource practices can improve economic performance: (1) employees must have the skills and knowledge that managers lack; (2) employees must have the motivation to apply them; and (3) the production system must channel worker efforts towards performance improvements (MacDuffie 1994; Ichniowski 1996; US Department of Labor 1993; and Ernst & Young 1995). In addition, some research has demonstrated a strong positive relationship between financial performance and the degree of integration between HR management and corporate strategy. For example, IBM-sponsored research emphasized the need for HR managers to change from an operational to a strategic role (Darling 1993, p. 4).

The heightened interest in evaluation of training and ROI specifically owes both to market pressures and internal forces within the training profession. As previously noted, market pressures have placed a premium on a skilled and flexible workforce, which in turn has significantly raised the importance of training. A cost-effective and rigorous ROI system, in which business strategic practices of planning and evaluation are applied to training, can greatly improve the quality, efficiency and effectiveness of training.

The focus on ROI also reflects the ongoing professionalization and rationalization of training departments and the drive for greater accountability. Internal competition for company resources places burden on the training department to prove training investments provide returns comparable to returns on uses of corporate capital. In an era of cost cutting, training expenditures must be made financially accountable. Given the increasing influence of Total Quality Management and ISO-9000 registration with their heavy emphasis on documentation and measurement, training departments will need to develop effective tools of benefit-cost analysis if they are to become integral to corporate strategy.

3.2 Industry Best Practices: The ASTD Benchmarking Forum

Perhaps the most compelling argument for the value of applying ROI to training is that the leading training firms are pursuing it. ASTD's Benchmarking Forum, a cooperative venture among companies with strong financial and organizational commitments to employee training, is gathering in-depth information about their own training organizations to identify training's best practices and generate comparative data to set a standard for their individual efforts. Motivated by internal pressure to show training's return on investment, Forum members have conducted research to determine: (1) who receives what kind of training at what price and for what purpose; (2) how to evaluate ROI of training to identify best practices; and (3) how to adopt or adapt training practices that clearly provide a competitive advantage.

3.2.1 Contributing to a System of Continuous Improvement of Training

There is a serious need for improvement in the effectiveness of training through monitoring and evaluation against clearly defined benchmarks. Evaluation and ROI has great potential to address the serious problem of poor knowledge and skills transfer from classroom to job (Broad and Newstrom 1992). Some estimates indicate that only about 20 to 30 percent of all training is being used on the job a month later, resulting in billions of wasted dollars. The problem is not that training is inherently ineffective, but that it is being poorly planned and implemented (Training 1996). Managers request courses without assessing what are the real needs of their employees. Supervisors neglect to reinforce employees' newly acquired skills.

3.2.2 Efficient and Effective Management

In an environment of rigorous evaluation, training objectives and content will become more lean, relevant, and behavioral with focus on monetary results rather than on the acquisition of information. It promotes better commitment of trainees and their managers, who become responsible for follow-up and ROI not just for meeting enrollment goals.

The unique industry characteristics of the construction industry make the challenge of ROI more daunting. They exacerbate problems of comparability and consistency in data; inputs cover a wide range of products that need to be converted into dollar amounts for purpose of comparison, raising the issue of real price determination and the search for an acceptable price deflator. Similarly, measuring productivity presents enormous challenges. A building project appears to be "a quagmire of skill differentiation and hand tool operations that converge at a unique point" (Finkel 1997, p. 83). Further, the fragmented nature of the industry makes it less likely that construction firms will respond to this challenge of ROI on their own.

3.3 Research on Returns to Training

What are the potential gains that ROI might enable firms to identify and capture? In neither the academic literature nor the business publications on this subject are there confident measures of the financial returns on training investment. Measuring the returns to training is still a research frontier, albeit an increasingly important one. Most existing empirical research concerns the effects of training on earnings and productivity growth for the individuals participating (Bishop 1988; Barron, Black, and Loewenstein 1989; and Holzer et al 1990). Relatively little academic research has addressed the effects of training on a broader range of worker and firm outcomes (e.g., quality, cycle time, sales, etc.). On the business side, the existence of a positive correlation between training and individual and firm gains is the prevailing wisdom. As John Bishop concludes: "Taken together the economic literature on training suggests that, as long as the company is initiating and paying for training, one can be pretty confident that most of these investments are profitable both for the worker and the firm" (1994, p. 24). However, this business confidence lacks a strong empirical foundation.

Preliminary findings from a general review of employer-provided training reveals several important gaps. Few studies have data sets large enough to allow econometric estimation of the unique causal effects of training, holding other elements of the human resource system constant. Most of the evaluation literature concerns public employment and training programs (Mangum 1990). Existing evaluations of training in the private-sector have focused mostly on the effectiveness of training for professional, technical, and managerial workers who currently receive the bulk of training.

Most existing economic literature concerns the relationship between education or training and individual wages and productivity. This follows from human capital theory developed by Theodore Schultz and Gary Becker, which posits that upward-sloping wage profiles reflect investments in human capital. Jacob Mincer extended the model to include employer-provided training. Mincer (1974) introduced several innovations which have had a profound influence on labor economics: (1) reinterpreting the age-earnings profile into the experience-wage profile and (2) shifting its emphasis to returns to on-the-job training (OJT) (Rosen 1992). According to human capital theory, OJT explains why the age-earnings profile is upwardly sloping over an individual's work life.

The Effects of Training on Worker Wages. Labor economists have found significant wage effects from education and training in support of human capital theory. Denison (1967) concluded that each year of education raises earning power by five to six percent with the effect tending to rise with the duration of education. Card and Kruger (1992) identified effects of similar magnitude. A 1995 national study found that a ten- percent increase in the average education of all employees in a firm is associated with an 8.6 percent increase in output for all industries, other things being equal. Note that this is double the increase in output (3.4) percent associated with a ten percent increase in the capital stock of a firm. There is also an 8 percent increase in wages associated with every additional year of schooling (National Center on the Educational Quality of the Workforce 1995).

Currently in the US, employer-sponsored training seems to increase wages of workers on the order of 4.4 to 11 percent. Barron, Black, and Loewenstein (1989) calculated that job training for new employees who have had no previous job training yields wage growth of 7.5 to 9 percent. Lynch (1991) found that the wages of young male workers who received one year of company training grew by 11 percent, while the wages of those who did not receive training grow by only 4 percent. Lynch concluded that slower productivity growth rates are the result of companies' poor training policies and poor training decisions made by workers. Lillard and Tan (1986) found for older cohorts that job training initially leads to wage growth of 10.8 percent, but this effect gradually diminishes over time.

The Effects of Training on Worker Productivity. Estimates of the impact of training on wages in the academic literature may be upwardly biased due to the self-selection of more "trainable" or motivated workers in workplace training. Therefore, it is equally important to identify and quantify the returns to firms of training investments in the form of productivity gains. Most research by economists focuses on the relationship between training and wage growth. Since wages are related to productivity, this kind of research may be useful by extrapolation to the relationship between training and firm performance. Yet economists are beginning to look beyond wages as proxies for productivity and to measure productivity more directly (Mangum 1990).

The Effects of Training on Firm Productivity. Industrial psychologists have conducted extensive research into the linkages between training, job knowledge, skills and abilities, and job performance. In practice, managers then indirectly and intuitively link these to firm performance. Yet this does not meet tests of scientific rigor.

Kochan and Osterman (1991) reviewed leading academic studies on the effects of training on organizational productivity, and found they provided "consistent and convincing evidence that (1) education and training are associated with significant productivity increases when their impact is examined in a production function context; and (2) training and associated human resource systems are associated with higher levels of productivity and quality in matched comparisons" (Bishop 1994, p. 23). However, the number of studies was very limited.

One study of manufacturing firms found that companies with formal training programs experienced a 19-percent greater rise in productivity (over three years) than those without such programs (Bartel 1994). Another study found that increased formal training significantly reduced the rates at which products had to be scrapped. Results of this study suggested that doubling the training per employee (from an initial average of 15 hours) would result in a 7-percent reduction in scrap (Holzer et al 1988).

Lynch (1994), in a summary of academic studies investigating firm performance, concluded that training increases productivity by 16 to 17 percent. This is a very high rate of return, but until researchers have a more representative sample of establishments in the US in which they can control for capital and other firm characteristics, the returns on training investment remain speculative.

Summary. In conclusion, results from the existing studies, according to a labor economist, are not generalizable. Sample sizes are too small; issues addressed vary too much across studies; designs are often flawed to the extent that they lack scientific rigor; and the connections to firm profitability are of suspect validity (Bishop 1994, p.19-20). Existing research suggests a strong relationship between training and firm performance, yet more is needed to provide a solid empirical base. Studies are especially needed with large enough data sets to allow econometric estimation that can isolate the effects due to training by controlling for other factors that influence firm performance.

From the business perspective, the training and development evaluation literature is just beginning to recognize the importance of measuring returns to investment in training and its impact on firm performance. In 1990, Anthony Carnevale and Eric Schulz summarized the ASTD's research on this issue. In survey conducted for this study, two out of three training managers reported they felt increasing pressure to show that programs affect the bottom line. However, only 20 percent of these same organizations conducted ROI studies, in part because they felt this type of evaluation "takes too much time or is too costly."

Currently, most reports in this area consist of broad overviews of the importance of measuring ROI (i.e., achieving such values as accountability, efficiency in allocating resources, and justification of training expenditures); individual case studies with limited generalizability; and various outlines of guiding principles and procedures for performing evaluations at the results level (Kirkpatrick 1996).

3.3.3 Research on Returns to Informal Training

The analysis of formal training returns is complicated by the complementary relationship researchers have found between formal and informal training. Each form of training is considered closely interdependent and, in the right environments, mutually reinforcing. Exclusion of informal training is therefore likely to overstate the effects attributed to formal training.

Bishop (1994) concluded that the largest extent of skill development results from learning by doing and informal training. Formal and informal training together account for only about 30 percent of the growth of a worker's productivity during the first two years on a job. Learning-by-doing accounted for the rest. For new hires, nine-tenths of the time that spend in training is watching others do the job or being shown it by coworkers and supervisors. Time devoted to training has a positive effect on wage growth, but these effects are substantially smaller than the productivity effects of training, suggesting that the labor market views many of the skills developed through informal learning as effectively specific to the firm. A recent series of BLS studies on informal training further documents the high incidence of various forms of informal training and learning. Its importance to firm performance has recently been detailed through field research at selected manufacturing firms (Educational Development Center 1998).

3.3.4 Returns to Training in Construction Industry

Since training in construction industry is offered in a wide variety of forms, the returns to training likewise varies significantly. For example, since 1982, the owners and managers of hundreds of contractors have empowered safety professionals to enact numerous safety-related training programs. In response to these efforts, the construction industry's illness and injury rate has dropped 26% between 1990 and 1995, and 14% from 1994 to 1995 for cases involving days away from work (Korman 1997).

In another example, recent CII research found that enhancement of supervisory skills can lead to improvements in safety, productivity, quality, absenteeism, and turnover. Owner investment in appropriate contractor supervisory training has a potential return conservatively estimated at 3 to 1 (Rogge et al. 1996). The level of this return echoes a finding of the Business Roundtable in 1982. Although research by the Roundtable uncovered no rigorous empirical studies of the returns to supervisory training in construction, it located case studies of major contractors, which suggested similar substantial returns of 3 to 1 (Business Roundtable 1983, p. 10).

In the early 1980s, Steven Allen conducted several studies on productivity in the construction industry. Some of these indirectly involve the effects on productivity due to training through union/nonunion comparisons. In one study, Allen found that a 7 percent reduction in union workers, who are trained through formal apprenticeships and journeyman upgrading, led to a 0.8 percent drop in productivity (Finkel 1997, p. 90).

Increasing interest in investment in training has been reflected in recent activities of the National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCER). NCCER contracted with researchers at the University of Florida to investigate returns to investments in training made by construction contractors. Through a mailed survey, the researchers contacted 750 firms to inquire about their interest and ability in providing data for the study. Thirty firms responded favorably about participating in the research. To date, case studies of specific craft training in two open-shop firms have been completed (Cox, Issa, and Collins 1998). In both cases, the returns to training investments made by the firms were quite positive, resulting from documented improvements in productivity, turnover rates, and absenteeism. Currently, the researchers are presently developing a series of briefing papers for industry practitioners and a guidebook of procedures to help construction contractors to conduct their own analysis of ROI to training investments.

3.4 Academic Approaches to Training Evaluation

Scientific rigor, enlarged scope, and hard data are the key advantages of the academic approach to training evaluation. Rigorous empirical analysis meets the test of validity, which is perhaps the most important characteristic of an evaluation instrument. A valid instrument measures what it is designed to measure. It also meets the test of reliability, which refers to the consistency and stability of an instrument. However, this kind of evaluation is generally very costly, requires considerable expertise and resources, and sometimes long time horizons. Further, it is often perceived by managers to be too intrusive and disruptive of their operations.

3.4.1 Academic Evaluation Techniques